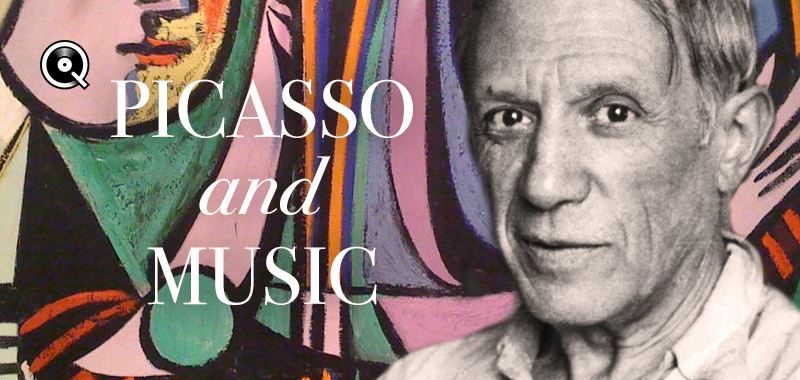

While he had been bathed in Andalusian melodies since his childhood in Malaga, it was in effervescent Barcelona, where he finished his studies in Fine Arts, that Picasso would really come to experience music, in the hectic depths of the Barrio Chino, its music halls, smoky bodegas, brothels and above all, the Els Quatre Gats, a tavern inspired by Chat Noir of Paris and thrilling with life, where pictorial revolution was discussed against a backdrop of guitars.

For Picasso, the guitar was a symbol of music. It is found in his works, broken up on the canvas, composed in collage or assembled out of boxes. New York's MoMa held an exhibition in 2010, Picasso: guitars 1912-1914. Flirting with surrealism, it developed into a series of aggressive collages. For centuries, the guitar has exalted the cante jondo. This form of song, which lies at the origin of flamenco recites coplas, short poems where metric and prosodic discord mimics the torments of the soul. Through speech and song, Andalusian Gitanos break free from misery and pain, to sing love and joy. These cries of emotion are everywhere in Picasso's work: in his women with cut and turned faces (Weeping Woman, 1937); in the euphoria of dance, in his empty-eyed saltimbanques (Family of Acrobats with Monkey, 1905). Manuel De Falla would also insist that a later friend of Picasso's was fascinated by flamenco: Stravinsky.

After Barcelona, Picasso went to Paris, the epicentre of the avant-garde. Leaving with his friend from the Fine Art school, Carlos Casagemas, he settled where he belonged: Montmartre. The rebels discovered la Bohème, the frantic rhythms of the French cancan, the Moulin de la Galette, the brothels and the taverns. In one year, Pablo painted Au Moulin Rouge, sketched the Cancan and made more than fifty other drawings, pastel or oil paintings rendering the hustle and bustle of cafés-concerts, those meeting-places for creatures of the margins. But in the autumn of 1901, the euphoria fell away with the death of Toulouse-Lautrec, a painter of the forgotten whom Picasso admired so much. He also recalled the suicide, six months earlier, of Casagemas, rejected by a dancer with whom he had had an affair. Here Picasso began his blue, melancholy period. Music, here associated with decadence, faded from his palette.

Create a free account to keep reading