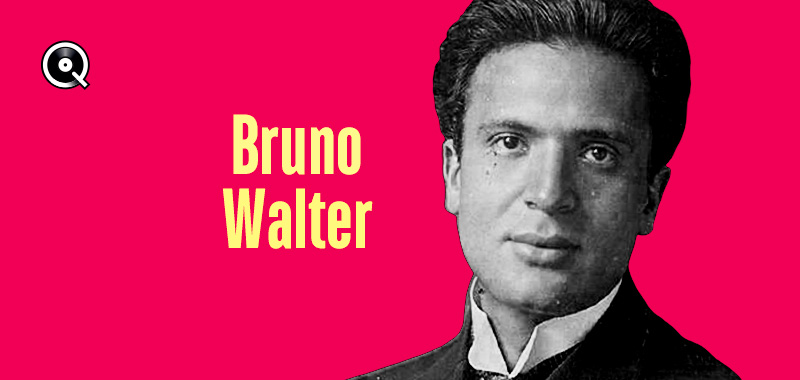

A friend of Stefan Zweig and of Thomas Mann’s family, with which he played chamber music (as was customary among cultured and well-off people at the time), Bruno Walter swapped his birth surname of Schlesinger for Walter in his youth, chosen as an homage to the Wagnerian hero Walther von Stolzing, the pure and idealist character from Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg (The Master-Singers of Nuremberg), well before the opera was appropriated as a piece of Nazi propaganda.

In fact, like so many others, that very regime would go on to push Bruno Walter to exile: the Nazis took everything from this now nomadic Jew. He left the chaos of Germany and became French for a while before heading to the United States to establish himself, where he was received as an important representative of grand European culture. Based in California, he continued to work and conduct, offering recordings filled with humanity and hope to the world. In fact, for Bruno Walter, music is imbued with great power. Among his writings, Of Music and Music-Making (published in 1935 and translated by Paul Hamburger in 1961 for Norton publishers in New York) effectively sums up his outlook: music is the synthesis of moral and aesthetic values, of the good and the beautiful.

At the helm of his career

Born in Berlin in 1876, Bruno Walter pursued very prestigious musical studies there, where his talents as a pianist were quickly identified. He turned his attention towards the orchestra however, after watching a concert conducted by Hans von Bülow, who had a profound effect on him. He was 17 years old when he was named the co-director of the Cologne Opera, then leader of the choirs at the Hamburg Opera the following year. It’s there that he met Gustav Mahler, then the director of the Hamburg institution. Walter’s emerging career led him to various different theatres, allowing him to practise and perfect his craft: Breslau, Pressburg, Riga and Berlin, where he became the Music Director in 1925.

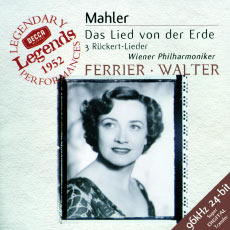

Bruno Walter became a Austrian citizen in 1911, having already worked for ten years alongside Gustav Mahler who called on his talent to support him in Vienna. An unbreakable friendship was born and Walter made it his life’s mission to spread his master, colleague and friend’s work for over fifty years, cogently imposing it so that it was fully appreciated in all of its worth. Premiering Mahler’s Ninth Symphony in 1912 in Vienna, he gave a historic version of the work in 1938 and again stereophonically in 1961, nearly fifty years later.

He was the director of the Leipzig Gewandhaus Orchestra when the Nazis put a stop to his activities. He nevertheless continued to conduct in Europe: in Salzburg in 1937 then in Lucerne in 1939 at the request of Ernest Ansermet, who had just had the idea of founding a music festival there. In 1946, Bruno Walter became an American citizen. He would eventually return to conduct in Europe: in Paris, London, Vienna and Edinburgh where he became an important figure in the beginnings of the Festival in 1947. He also conducted the Opéra de Paris and participated with many other big names of the era in the Œuvre du XXe siècle festival, a multi-arts event created by Nicolas Nabokov in 1952.

An invaluable discographic legacy

Conscious of Bruno Walter’s historic and artistic value, the record houses were always after him to record his interpretations. After the war, he recorded the essential parts of his discography with , then CBS (now amalgamated into Sony Classical): Mahler of course, but also some unforgettable recordings of symphonies by Mozart (the last few), Beethoven, Brahms, Schubert and Dvořák as well as pages from Richard Wagner and Richard Strauss.

His first American recordings were done in Manhattan with the New York Philharmonic Orchestra of which he was the Musical Director from 1947 to 1949, following in the footsteps of Gustav Mahler, who headed the orchestra from 1909 until his death in 1911. In the 1950s, Columbia (CBS) had the means and the power to create its own orchestra up to the standard of the great European masters: mainly Bruno Walter, but also Sir Thomas Beecham, Igor Stravinsky and the young Americans Robert Craft and Leonard Bernstein.

The musicians of the Columbia Symphony Orchestra were handpicked, and were either independent or part of the New York Philharmonic or the Los Angeles Philharmonic, depending on whether the recording was taking place on the east or west coast of the United States. What the orchestra has in quality it lacks in real personality: void of tradition, it relies on the art, patience and kindness of somebody like Bruno Walter to be infused with any colour or style. The Columbia Symphony recordings are nearly all recorded stereophonically from the end of the 1950s until the death of the conductor in 1962. Having not aged a jot, they resound today for ears accustomed to a certain sonic voluptuousness.

Some of the albums contain extracts of rehearsals, including a certain famous Symphony n°36 (Linz Symphony), re-edited today as a prelude to its complete recording instead of the later version in stereophonics. This pairing allows one to passionately follow the bright way this conductor approached Mozart’s music, his way of making every desk sing out and the almost friendly proximity he maintained with the orchestra, calling some of the musicians by their names (‘Mr. Bloom’, the first oboe) or more generally but still with the utmost care and goodwill: ‘Gentlemen’, or ‘My Friends’. It’s a fantastic lesson in modesty and concern for playing together without a crisis of authority, as Claudio Abbado would state later on.

Create a free account to keep reading

![Mozart, W.A.: Zauberflote (Die) [Sung in English] [Opera] (Walter) (1956)](https://static.qobuz.com/images/covers/71/00/4015023160071_230.jpg)

![Mozart, W.A.: The Marriage of Figaro [Opera] (1937)](https://static.qobuz.com/images/covers/80/07/8021945000780_230.jpg)