In jazz and blues, the genres’ most satisfying moments can be found in their middle ground—that smartly rugged musical space between the Mississippi jook joint and West Village club. Of course both of these interdependent traditions spring from the Black American experience, and jazz has frequently utilized the streamlined and adaptable song forms of blues. What’s more, improvising over blues chord changes with charm and presence has often been seen as a jazz musician’s certificate of authenticity—dominion over elusive fundamentals of time and storytelling. A deity of modern jazz, Charlie Parker played the blues with a command and sincerity that gave his breakneck bebop an earthy magnetism. In blues, the big-band devotee B.B. King genuflected to jazzmen like Charlie Christian and Django Reinhardt, subsuming fragments of their breathtaking methods into his legendary economy. Duane Allman perfected his long-form improvising by listening non-stop to Miles and Coltrane. Many instructional books and online lessons aim to teach guitarists how to spice up their bar-band blues licks using jazz harmony. Jazz is aspirational.

But defining jazz as intellect or ambition and blues as soul or simplicity doesn’t cut it: Robert Johnson’s Delta blues was a wizardly technical achievement, and plenty of fine jazz improvisation has happened over one- and two-chord vamps. Both genres are capable of transforming one’s worldview. It’s more accurate to think of blues, with its 12-bars and finite harmony, as an aesthetic of familiarity and solace, and jazz, with its learned bent toward progress, as a push into uncharted territory.

Bessie Smith with Louis Armstrong - “St. Louis Blues” (1925)

Chronologically and stylistically, Bessie Smith fell on both sides of the jazz-blues divide in such complicated ways that academics could hold a symposium on the topic. (Maybe they already have.) Was she the finest of the vaudeville tent-show performers—the only singer Ma Rainey really had to worry about? (Her moniker was the Empress of the Blues, after all.) Or was she ground zero for jazz divadom, a vocalist whose eloquent power and precision informed every blues-capable jazz singer to follow her, from Billie Holiday to Dinah Washington to Dee Dee Bridgewater? She was both of course, a transitional figure between the partytime polyphony of the ‘20s and the ballroom focus of the swing era. Smith was also an early example of the principle—which still stands—that says great jazz singers can be spotted via the instrumental company they keep, and she recorded and performed with Louis Armstrong, Coleman Hawkins, Sidney Bechet, Chu Berry, James P. Johnson and other heavyweights. On “St. Louis Blues,” she and Armstrong engage in a spine-tingling dialogue.

Eddie Lang & Lonnie Johnson - “Blue Guitars” (1929)

To hear the guitarist Lonnie Johnson’s 1920s recordings is to have much of what you believed about jazz, blues and guitar history upended. The juicy bent notes and fleet, horn-like licks—how did this music unfold when Charlie Christian was still a kid, and B.B. King was a baby? A profound, if unsung, progenitor of the blues-based, single-note technique that evolved into rock-guitar heroics, the Louisiana-born musician ascended in blues and jazz, recording with Armstrong, Ellington, Victoria Spivey and the pre-Django jazz-guitar god Eddie Lang, with whom he cracked the color barrier. By midcentury he’d become a sort of regal songster with a debonair singing voice and a wide-ranging repertoire, who scored a hit with 1948′s “Tomorrow Night,” famously covered by Elvis for Sun Records. He was later propped up by the American roots revival that thrived in the ‘60s. Johnson resented being pigeonholed as a country-blues or folk performer, for good reason: He was proudly urbane, performing “city blues” that prefigured R&B balladeering and offered masterful bursts of flatpicked guitar ornamentation. Spin the Lang duet “Blue Guitars,” featuring Johnson on 12-string—front-porch blues with a bit of pre-doo-wop DNA.

Charles Brown (Johnny Moore’s Three Blazers) - “Drifting Blues” (1945)

The singer and pianist Charles Brown, who hailed from small-town Texas but became an icon of cosmopolitan West Coast blues in the 1940s, made music for date-night, lovers’ lane ambiance. His twilit tenor was masculine yet tender, and his consummate piano playing exhibited both a downhome touch with the easygoing smarts of the Nat Cole school (despite the runaway virtuoso Art Tatum ranking among his musical heroes). In the guitarist Johnny Moore’s Three Blazers and later as a solo artist, Brown relished blues forms and harmony at slow tempos, exerting a maturity and composure in songs that L.A. nightclub audiences enjoyed like pop music but connected to the cultured allure of modern jazz. “Drifting Blues” was a smash hit—his other hit you already know is “Merry Christmas, Baby”—and it remains a totem of California cool, a club-blues standard that laid a foundation for the R&B of Ray Charles, Floyd Dixon and others.

Dinah Washington - “Trouble in Mind” (1952)

A tragic tempest of charisma, Dinah Washington boasted an adaptability that made her a pivotal figure in American song. Coming of age in both gospel and the forbidden din of nightspots, the Queen of the Blues attacked her too-brief career with a voracious purview: jazz, R&B, vocal pop from sharp to saccharine or, of course, a reliable 12-bar. There, her genius lied in balancing her smoldering aura with her finishing-school perspicuity of voice. (She couldn’t have communicated a lyric more directly if she simply read it.) Like Bessie Smith, to whom she paid distinctive tribute, Washington did pioneering work for Black women who found success by seeing American music as one interconnected idiom; her impact can be heard in Aretha Franklin (Washington was a family friend), Nancy Wilson, Nina Simone, Diana Ross, Dianne Reeves, Vanessa Williams, Jennifer Hudson, the list goes on. Even Beyoncé's Cowboy Carter finds precedent in a recording like Washington’s meticulous interpretation of Hank Williams’ “Cold Cold Heart.” On this take of the blues standard “Trouble in Mind” with saxophonist Ben Webster and Kind of Blue drummer Jimmy Cobb, Washington’s romantic partner, her time-feel is stupendous, and her taut, high phrases can recall her beloved Billie Holiday. Washington’s death at age 39 in 1963, the result of mixing booze and diet pills, is one of jazz history’s most woeful early exits.

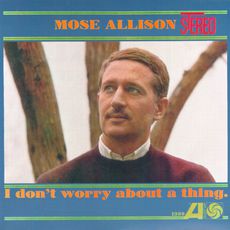

Mose Allison - “I Don’t Worry About a Thing” (1962)

Mose Allison was a singer, songwriter and pianist whose own career remained respectably modest even as the magnitude of his impact on pop history expanded. It’s hard to imagine the best literary-cynic songsmiths of the 1970s—Tom Waits, Warren Zevon, Donald Fagen, even Randy Newman—existing without his template for sardonic nightclub tunes. And his rootsy sophistication knocked out the U.K. R&B and blues-rock gods of the ‘60s, among them The Who, The Yardbirds, Georgie Fame and Van Morrison. His songs became familiar rock fare, sometimes taken to volumes that made heavy metal possible. (See The Who’s Live at Leeds version of “Young Man Blues,” or Blue Cheer’s “Parchment Farm,” a curiously spelled take on Allison’s recasting of Bukka White’s “Parchman Farm.”) But the reason Allison is here has little to do with legacy and everything to do with a cultivated nonchalance that evokes his hero Charles Brown. Born in the Mississippi Delta to a father who played stride piano, he later made the scene in New York and recorded with Stan Getz, Al Cohn, Zoot Sims and other paragons of ‘50s jazz. That duality is precisely what his own records reflect. “I Don’t Worry About a Thing,” a wickedly clever original blues, makes you tap your foot and order another drink, all while Allison swings you to sleep.

Kenny Burrell - “Chitlins Con Carne” (1963)

There’s a general misunderstanding around guitarist Kenny Burrell’s bestselling 1963 album Midnight Blue, an absolute essential for the jazz and blues record shelf, and, as Burrell has said, the favorite Blue Note release of Alfred Lion, who co-founded that institution. (Full disclosure: I’ve worked directly with Blue Note as an editor and copywriter, though Midnight Blue requires no favors.) It’s often viewed as a laidback blowing-session sort of LP, a mellow, casual portal for blues and rock fans making their way toward jazz. In reality, Midnight Blue is a purposeful, conceptual masterpiece that only came to be because Burrell took a more forgiving pit-orchestra gig and curtailed his nonstop schedule of session work.

With time to rest, write, plan and execute, he devised a program consisting mostly of memorable original blues tunes, played by an ingenious quintet: tenor saxophonist Stanley Turrentine, bassist Major Holley and drummer Bill English, sans piano but with Ray Barretto on conga. The results boast a terrifically uncluttered soundstage, with plenty of harmonic air and an emphasis on percolating grooves. Burrell’s background made him uniquely suited to matching blues candor with jazz urbanity: Among the most soulful of jazz modernists, he grew up in Detroit’s blues-soaked Black Bottom neighborhood and showed tremendous drive, mastering bebop language, making his first recordings with Dizzy Gillespie (an informal mentor), studying composition and theory in college, and taking lessons in classical guitar. By deftly flavoring his bebop-rooted approach with electric-blues comforts, he became the quintessence of jazz-blues and hard bop; his coolly lyrical sound remains one-of-a-kind, even after so many imitators. Burrell’s signature tune, " Chitlins Con Carne, " is a smoky minor blues set atop Latin rhythm. Often covered—including must-hear versions by Stevie Ray Vaughan and Junior Wells with Buddy Guy—it’s the kind of magical vehicle that seems to do most of the work for an improviser.

Jay McShann - “Confessin’ the Blues” (1977 recording)

It’s a jazz-writing doctrine that any blurb on pianist-singer Jay « Hootie » McShann must begin with a mention of how Charlie Parker got his professional jump-start in his band, which cemented the bop pioneer’s bluesy center of gravity and earned him his first recording credit. Less often mentioned is the cinematic nature of that encounter, how McShann heard bird’s sound wafting down the street in Kansas City and discovered the genius-in-progress the teenager had been honing in the Ozarks.

But McShann was an American treasure in his own right, who delivered Kansas City’s brand of swing to audiences throughout his life, including for many years after Count Basie had died. As far as his actual sound, how do you describe a sip of cold beer after a long week? He combined blues, swing and boogie-woogie—McShann studied Pete Johnson around town—into one life-affirming brew, and his cozy singing voice oozed charm. The fact that McShann ended up living in Kansas City on a whim, when he was originally bound for Omaha, gives his story a tinge of novelistic destiny. This 1977 recording of his ‘41 hit " Confessin’ the Blues " features a band of maestros along with a twentysomething John Scofield, himself a superb jazz-blues stylist.

Hank Crawford & Jimmy McGriff - “Jimmy’s Groove” (1990)

Truth be told, several hard-working organists from Philadelphia—the Hammond B-3′s jazz mecca—could have occupied this spot: the master technician Jimmy Smith, of course, or the Queen of the Organ, Shirley Scott, or Bill Doggett of " Honky Tonk " fame, or the Mighty Burner, Charles Earland, among others. All arrived at spirit-filling amalgams of blues, jazz, R&B and gospel. But Jimmy McGriff separated himself by attracting a contemporary soul-jazz audience while insisting—in interviews and in album titles—that he was a blues organ player. Even if he didn’t reach Smith’s level of bewildering virtuosity, he was in fact an advanced player who knew his way around a standard, studied at Juilliard, and revered big-band music, especially Count Basie. But his greatest flair was for 12-bar saunters and churchy R&B rave-ups. Dig " Jimmy’s Groove, " a swinging midtempo blues featuring McGriff with his jazz-blues comrade-in-arms Hank Crawford on saxophone. It’s so practical in its ambitions, yet so well conceived, that it’s extraordinary.

Cassandra Wilson - “Come on in My Kitchen” (1993)

In the 1990s, jazz musicians seemed to want to expand the concept of repertoire in earnest—pushback, perhaps, against the absurd notion that once a musician can play bebop, other interests aren’t worthy. On her Blue Note debut, 1993′s Blue Light ‘Til Dawn, the singer Cassandra Wilson took on R&B, Van Morrison and Joni Mitchell, as well as, conspicuously, two Robert Johnson tunes. Wilson and her producer Craig Street, who suggested Johnson, did not aim to jazzify these Delta-blues staples; instead, they allowed Wilson’s cavernous moan free rein throughout austere arrangements, honoring the ghostly edge of Johnson’s performances. Wilson’s album, with its progressive-folkie bent, seemed to ask, what’s a vocal-jazz record? What’s a vocal-jazz singer? Challenging stuff, but Wilson was simply telling her story—a Mississippi singer, born into a jazz-loving home, who wrote her own songs, covered Mitchell, Dylan and the like in high school and later came under the spell of Betty Carter and New York jazz’s bleeding edge. On her take of Johnson’s " Come on in My Kitchen, " clacky rhythm and Tony Cedras’ accordion function like a smoke machine, blowing eerie atmosphere around Wilson’s oceanic vocal.

NEA Jazz Masters: Cassandra Wilson (2022)

National Endowment for the ArtsRobben Ford - “Birds Nest Bound” (2013)

A guitar hero’s guitar hero, Robben Ford burrows into a groove and then makes all the right moves, peaking when he locates the sweet spot between fusion pyrotechnics and rocking electric blues. He’s another example of a musician whose life story can be heard in one expertly framed chorus of swing or shuffle rhythm. Enamored of cool-jazz saxophonist Paul Desmond, he played alto as a kid before switching to guitar at 13 and being struck by the lightning bolt that was Mike Bloomfield. Early professional experience with bluesmen Charlie Musselwhite and Jimmy Witherspoon seemed to set a path, but soon enough Ford fell in as a member of the L.A. Express, excelling in the pop era when studio aces ruled the roost and, in the case of the Express, backed intellectual singer-songwriters like Joni Mitchell. Ford was also the catalyst for fusion all-stars Yellowjackets and performed in Miles Davis’ band in 1986, but he’s built his career mostly as a guitarist and singer whose complementary passions for hard blues and Coltrane are never far from the surface. This take on Big Joe Williams’ " Birds Nest Bound " flaunts plenty of his slyly assured soloing, with a fantastic band including organist Larry Goldings and drummer Harvey Mason.