Music history might take a while to play out the way we expect, but eventually time and narrative will bear out some exceptional truths—even ones that seem like hot takes at first. So maybe it still seems at least a little blasphemous to state that, fifty years after its first canonized and documented origins, hip-hop has entered the permanent musical lexicon—like jazz in the early twentieth century and rock ‘n’ roll in the postwar era. Yet the genre has proven to be such a resilient and mutable art form that it has become one of the primary evolutionary and creative drivers of popular music to this day. Jazz was grappling with its own commercial relevance 50 years after the early breakthroughs of Duke Ellington, and rock was beginning to consider the same fate half a century after Chuck Berry’s revolution. But hip-hop, like the rhythm and blues traditions that it spun off from, keeps ascending into new forms while maintaining at least a recognizable connection to its primordial origins in 1970s New York.

There were precedents as far back as there were disc jockeys. Early ‘70s pioneers like Grandmaster Flowers and DJ Hollywood combined radio-derived rhyming patter with an itinerary of crowd-moving dance-party jams, while the nascent club culture that would eventually evolve into disco was tinkering with the concept of creating a sound driven by seamless beatmatching and extending instrumental grooves into deeper excursions eventually dubbed “remixing.” But after a Jamaican immigrant, a South Bronx resident going by the alias DJ Kool Herc helmed a rec room back-to-school party gig—held on August 11, 1973, as reliable a birthdate for hip-hop as any—his combination of hooky catchphrases and nonstop extended mixing of heavy instrumental funk percussion breaks hit the youthful crowd with such force that it felt like an entirely new sort of catalyst. The parameters of the genre would be fully written within half a decade, and while the particulars would change—eventually the DJ and the MC would split off into more dedicated roles—the style would become easily recognizable by the end of the ‘70s. The fundamental elements of the hip-hop club-going experience—rapping, DJing, and the elaborate dance moves that those drum breaks inspired (hence breakdancing)—were soon bolstered by a visual style in the elaborate and colorful typography and pop art that sprung up from graffiti culture.

By the time New York’s other music and art scenes caught on during the cusp of the ‘80s, where the intermingling of South Bronx hip-hoppers and downtown punk rockers led to curious crossovers, hip-hop had found a way to evolve on its own terms from a club phenomenon to a small but growing segment of the post-disco-crash music business. That led to a bit of early compromise: considering the copyright-minefield aspects of rapping over looped James Brown and Dennis Coffey recordings, the foundational DJ was largely sidelined for live-band re-recordings and original compositions. With so many established rappers and DJs skeptical of being commercially compromised, it took an emerging label’s quickly assembled crew of ringers to take that first step on wax. And while Sugar Hill Gang’s pioneering 1979 hit “Rapper’s Delight” is still a contentious topic to this day—both its lyrics and its groove were partially lifted from first-gen rapper Grandmaster Caz and disco hitmakers Chic without permission—it was also a hard-to-resist first salvo for the emerging genre. It spurred countless follow-ups from just about everyone else in the scene, a canon building itself out of competitive artistry and creative possibility (and, of course, the potential for a truckload of new-music-craze money).

If the then-recent industry and audience burnout over disco was any indication, this new rap movement was keenly aware of what could happen when a sound gets stagnant the moment it hits critical mass. Tectonic stylistic shifts happened right when they were needed. First, the slippery-flowing, amiable, uptempo disco-funk style of hip-hop’s origins became relegated to “old school” designation in the mid ‘80s after Run-D.M.C. defied it by rapping aggressively over stripped-down yet hard-hitting mid-tempo drum machine beats. Then, as that Queensbridge crew became rap’s first platinum act, their eventual usurpers picked up on their approach and found endless new angles to it. The prominent motivators of lyrical one-upmanship and the relentless search for increasingly esoteric-yet-trendsetting breaks lead to a late ‘80s creative explosion that fans marked as hip-hop’s golden era.

While that period seemed like it could’ve been sustainable just from the battle-rapping and DJ scratch-routine fundamentals that drove the sound at its New York-driven core, it was the steady emergence of artists who defied the potential for regional and stylistic provincialism that made this era so revered. Hip-hop started as a distinctly N.Y.C. phenomenon, but the street-rap influence of artists beyond the five boroughs—from Philadelphia’s Schoolly D to Los Angeles’s Ice-T—would spread from coast to coast and invite numerous new regional permutations. After countless storytellers and punchline slingers pushed the boundaries of hip-hop’s subject matter from crowd-pleasing hooks to feats of evocative, elaborate songwriting, it became clear there was room for all kinds of personae and philosophies: political firebrands like Public Enemy; tough-yet-perceptive gangsters like N.W.A; Afrocentric feminists like Queen Latifah; artful bohemians like De La Soul; comedic postmodern wiseasses like the Beastie Boys. And while the air of sex-and-violence controversy and moral panic hung over hip-hop as the ‘80s flipped to the ‘90s, it was also hard to look at the likes of MC Hammer going platinum more than ten times over and still consider the genre on the whole to be a purely niche movement, much less a passing fad.

But things really started accelerating into exciting new turf when more and more producers started getting their hands on samplers. While early rap was usually backed by either studio bands or drum machines, many beatmakers had worked on methods that served to more easily replicate the break-extending role of the DJ, even resorting to painstakingly made “pause tapes”—beats made using dual cassette decks to record a sample which was then paused and rewound to record the sample again, creating a beat or loop of the desired length. When producers like Marley Marl started figuring out how to create, replicate, and then massively transform loops and beats using machines like the E-mu SP-12/SP-1200 series of the mid-to-late ‘80s, the floodgates were opened. If you had a sampler and a good record collection, you could make unprecedented compositions from a seemingly limitless galaxy of source material. The Bomb Squad turned the James Brown Revue into a sonic assault that sounded nearly as punk as it did funk. A Tribe Called Quest retrofitted classic ‘60s and ‘70s soul-jazz into granite-heavy boom-bap. And Dr. Dre built an empire by elaborating on the analog-synth sounds of classic funk groups like Parliament and Ohio Players. The industry took notice, pulling out their Rolodex of copyright lawyers. While sampling would eventually become cost-prohibitive and logistically dicey—just about every instance would need to be cleared through the sampled artist’s songwriters and labels—it never really disappeared: the megastars could afford it, and the underground just kept digging up increasingly hard-to-source obscurities from their crates. Creativity and ingenuity would continue to outpace the lawsuits.

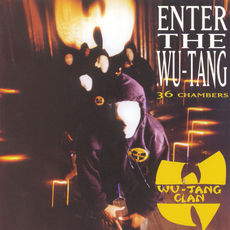

The asking prices for samples got so high in part because record companies saw hip-hop as an extremely reliable source of income. When Nielsen’s SoundScan sales-tracking system revealed just how commercially lucrative hip-hop actually was, it officially cultivated the era of the rap megastar—not just for the pop-friendly likes of MC Hammer, but for a wide array of previously unlikely icons who might have otherwise been considered to have limited regional or underground appeal. Sometimes it felt like an inevitability: the rise of gangsta rap in late ‘80s meant a near-instant household name like Snoop Dogg was not just possible but definitive. And sometimes it felt like a total ambush, like how the fiercely idiosyncratic ensemble cast of the Wu-Tang Clan would saturate the ‘90s with some of the most uncompromisingly grimy-sounding and lyrically complex hip-hop of the decade.

The business would boom so loudly that the stakes eventually became cutthroat. This was best witnessed in the havoc of the 1995 Source Awards, where the rap magazine’s all-star showcase saw L.A.’s Death Row Records head Suge Knight angrily taunt N.Y.C. mogul Sean “Puff Daddy” Combs, turning an already competitive coast-vs.-coast cold war into a conflagration. The immediate future saw a grim and cruel conclusion to that conflict, a beef that claimed the lives of two of rap’s most brilliant stars, 2Pac and the Notorious B.I.G. History would also soon bear out another of the show’s more infamous moments, namely the demand expressed by OutKast in response to being booed for winning best new artist: the South got something to say.

Hip-hop ended its second decade in flux: the business was more lucrative than ever and culturally dominant enough to inform rock artists from Beck to Rage Against the Machine, but debates would rage as to whether its biggest stars were doing right by the genre. In retrospect, it’s pretty stark to consider the stylistic gulf between the opulent, hook-driven megahits of the big-budget “shiny suit” era and the more experimental and lyrically intricate cult classics of the bustling indie-rap underground that opposed it. Maybe that made the success of Eminem, one of the few white artists to earn some legitimacy in the traditionally Black art form, such a surprise: he spit like a hyper-technical underground backpacker, but had the co-sign of Dre, TRL (Total Request Live), and an army of both hip-hop hardcores and alienated suburban teens behind him. The onset of the instant-access era of music consumption in the 2000s—first through file sharing, then YouTube—also meant the entry point for emerging sounds and trends was significantly easier for listeners in search of the new and novel, making the mainstream/underground divide increasingly irrelevant. Independent mixtapes would start to break artists before the industry even noticed them, and frequent incursions would be made by against-the-grain regional sounds like the California Bay Area’s woozily unpredictable hyphy or the synths-and-808s hypermaximalism of Atlanta crunk. Even as the record business stumbled over itself trying to figure out its internet-mutated future, hip-hop maintained its cultural dominance, minting a constant string of inescapable one-off novelties and long-term megastars alike. Not everything endured—for a stretch of the mid-to-late 2000s, it seemed like half the big hits were crafted to sound best as custom ringtones for the pre-smartphone era—but at least it all felt wildly up for grabs.

Notorious B.I.G. - Brooklyn Freestyle at the age of 17 (1989)

Fernando Quintero GonzálezOnce we hit the social media era and critics started lamenting the end of the monoculture, those concerns were simultaneously reflected in hip-hop’s increasingly niche-carving iconoclastic diversity and countered by a new generation of attention-demanding icons. The 2010s gave us the omnipresence of stanbase-cultivating, meme-driving celebs like Drake, Migos, and Cardi B, but it also gave rise to artists whose impact and importance was harder to quantify from either record sales or viral fame. Whether it was the enfants terribles turned artful revolutionaries in Odd Future, the hybridized N.Y.C. underground-meets-ATL street superduo Run the Jewels, or the bloodstained-couture luxury violence of Westside Gunn’s Griselda collective, countless artists emerged who pushed a distinct vision above everything else, and still wound up popular enough to prove that kind of risk-taking still resonated. Any musical genre still capable of providing that kind of duality—being both commercially successful and able to cultivate a healthy, unpredictable sense of myriad future directions—has more than earned its 50-year climb to the top.

Standout Tracks

Spoonie Gee and the Treacherous Three - “The New Rap Language”

Even as early as 1980, it wasn’t enough to just acknowledge that rap was a new language in itself—it was that this language needed to keep evolving and developing into something spectacular. The Treacherous Three—L.A. Sunshine, Special K, and eventual legendary breakout star Kool Moe Dee—are in era-peak form here, delivering party-rock entreaties, self-big-ups, and quick mic-passing rapport with a then unprecedented, still-impressive level of uptempo lyrical agility.

Grandmaster Flash - “The Adventures of Grandmaster Flash on the Wheels of Steel”

Rap wasn’t a hard sell, but a DJ scratch routine? Who’d buy a record of a record? Still, Sugar Hill gave turntable pioneer Grandmaster Flash a chance to show off his scratch routine on wax, and it paid off big as the first widely available example of a cut-and-scratch record that really showed off the strengths of hip-hop DJing. It’s a fun, fast-moving ride, from his thanks-for-the-namedrop nod to Blondie’s “Rapture” to the clever juxtaposition of the “Rappers Delight”-interpolation of Chic’'s “Good Times” and Queen’s Nile-type beat of “Another One Bites the Dust.”

Run-D.M.C. - “King of Rock”

Run-D.M.C. presided over a lot of changes from first-wave old-school—the gradual shift from a singles-only genre to include LPs as a medium of choice, the fashion sense that shifted from punk-funk costumes to everyman streetwear, and a sound that valued heavy impact over slippery groove. This hard-rock hybrid was the titular highlight of their second LP, big enough to build a Live Aid performance around it. They might not have fully crossed over until their cover of Aerosmith’s “Walk This Way” a year later, but all the potential in the world was right there from the first 808 clap.

Public Enemy - “Fight the Power”

The same decade defined by hip-hop’s emergence was also marked by Reaganomics-induced struggle, anger, and rebellion, especially in the Black community. Public Enemy was a revolutionary product of that mindstate, and thrived off a singular combo of Chuck D’s haymaker voice preaching defiant, resilient resistance, Flavor Flav riffing as his comic-profound hype man, and the Bomb Squad supercharging classic soul into an innovative, sample-based sonic assault. And as the title theme to Spike Lee’s sociological masterpiece Do the Right Thing (1989), “Fight the Power” felt like a mission statement: don’t just move the crowd, point them where to go.

Dr. Dre ft. Snoop Dogg - “Nuthin’ but a “G” Thang”

The sonic gulf between East Coast and West Coast hip-hop wasn’t always so distinct—at least not until California-based producers from Too $hort to DJ Quik started to incorporate their own distinct ‘70s synth-funk influences on the genre. N.W.A alumni Dr. Dre earned the most acclaim for the way he shaped that slow-gliding, top-down, Minimoog-and-ARP-drenched vibe into a sound eventually christened G-funk, though it helped that his biggest hit from the era-defining solo debut The Chronic had the impossibly charismatic presence of future icon Snoop Dogg to add that last definitive piece of gangsta panache.

Wu-Tang Clan - “C.R.E.A.M. (Cash Rules Everything Around Me)”

Every element that made East Coast hip-hop so compelling in the late ‘80s and early ‘90s—vivid storytelling, diabolical punchlines, a sense of power and strength maintained through times of adversity—was pushed to its artistic limits when RZA’s collective of hungrily ambitious outsiders invaded from Shaolin (a.k.a. Staten Island). The Wu-Tang’s combination of hardcore street rap, philosophical depth, emotional introspection, lyrical ingenuity, and stunning, counterintuitive beats might’ve sounded strictly underground, but instead they built a pop-culture empire that still stands as the blueprint not so much for defying what the industry demands but for exceeding it.

Missy Elliott - “Get Ur Freak On”

Hip-hop started as dance music, and there would always be hits that worked in both worlds no matter how far apart they grew. At the turn of the millennium, after a decade of tectonic shifts in rave culture, it would take a real daring brain trust to figure out how to make that all work in a rap context. Missy and Timbaland turned out to be that brain trust, and their delirious peak is this bhangra-drum-’n’-bass fusion that still sounds like one of the most deliriously futuristic rap songs to hit the Top Ten on both sides of the Atlantic. Missy’s voice in particular is a marvel—cooing, belting, snarling, warping into operatic surrealism, and blurring the lines between MC and singer so thoroughly it makes both roles sound limitless.

UGK ft. OutKast - “Int’l Players Anthem (I Choose You)”

By the mid-2000s, “Southern rap” had shifted from a provincial sound to a foundational one, and this summit by two of their respective regions’ all-time greats is a powerful example of why that happened. Port Arthur, Texas’s UGK and Atlanta’s OutKast do what their home turfs did best: shape their drawls into nimble, flowing, playful instruments in themselves; deliver lyrics that teeter between comedic ingenuity and gangsta intensity; and come across like the kind of extravagantly stylish, endlessly cool players that their sonically invoked ‘70s hustler forebears would envy.

Kendrick Lamar - “Alright”

The artist with the strongest claim to Best Rapper Alive in the 2010s grew up with the atmosphere of Dre’s G-funk, developed a style simpatico with the soulful boho-meets-hood depth of OutKast, and drew off that background and style to deliver hip-hop’s biggest protest anthem since Public Enemy’s peak. But Kendrick’s L.A.-via-everywhere appeal isn’t just the synthesis of his rap ancestors, it’s his mixture of the deeply personal perspective and the outwardly collective spirit that spoke to the hopes and fears of his millennial cohort—one he expresses with virtuosity and swagger, defiance and solidarity, artfulness and hooky immediacy, all over a Pharrell-Sounwave beat that hovers between soul jazz and trunk-rattling bass.

Cardi B - “Bodak Yellow”

Social media accelerated musical engagement in unusual ways: it’s one thing to have a hit, but it was even more important to have a meme. Like all good memes (and a lot of older hip-hop traditions), Cardi B broke through by riffing off someone else’s idea—the flow Kodak Black used on his own debut track “No Flockin’” and making it thoroughly her own, regardless of regional affiliations or stylistic pigeonholes. But aside from the ensuing commercial-viral success that made her one of the highest-selling, most-played female rap artists in history, “Bodak Yellow” is also an infectious, dizzying immersion in her trap-informed, singsong-warping cadence delivered with the kind of supreme confidence that she wields like her birthright.