Nineteen seventy-three was a year of great change in the United States. The Vietnam War was finally winding down. The ongoing Watergate scandal was consuming the Nixon administration, and political corruption led to the resignation of Vice President Spiro Agnew. Roe v. Wade overturned state bans on abortion, leading to a new era for women. The U.S. launched its first space station, but it was also in an oil crisis. And “Little” Stevie Wonder, at age 23, released Innervisions, his 16th album—one that would capture the restlessness of the times and have an incredible influence on music moving forward.

It also came at a time of change for Motown, the label that gave Wonder his professional start when it signed him at 11 years old. After the Detroit Rebellion of 1967, Motown moved to Los Angeles. And one of its biggest acts, Marvin Gaye, took a sharp left turn from the label’s hit-making candy-coated R&B and soul in 1971 with his groundbreaking What’s Going On. The eye-opening messages of the title track—an emotional condemnation of police brutality—and “Mercy Mercy Me (The Ecology),” one of the first mainstream hits that expressed heartache over our environment, stirred something deep in Wonder.

Here is how the five most important tracks on Innervisions came to be—and why they still matter today.

“Living for the City”

You can hear Gaye’s influence on the now-classic “Living for the City,” a seven-minute-plus song about a Black boy born poor and destined to face discrimination in Mississippi. After watching his mother scrub other people’s floors and his father work 14-hour days for “barely ... a dollar”—and seeing his own stagnant future (“To find a job is like a haystack needle/ ‘Cause where he lives they don’t use colored people”)—he is determined to join the Second Great Migration and find a new life in New York City.

The Fender Rhodes electric piano starts off moody, panning in a head-spinning way to induce disorientation, then the TONTO synthesizer comes in so brassy and bright—a sign of hope. (It should be noted that TONTO—The Original New Timbral Orchestra—developers Malcolm Cecil and Robert Margouleff were on hand for programming the instrument and co-producing the album with Wonder.)

In the middle, the song turns into a one-act play: You hear the bus bound for NYC pull up and carry him away … to a life of accidental crime and a 10-year prison sentence. It’s high-tension, complete with samples of teeming streets, sirens, the slam of a cell door.

Wonder’s brother Calvin Hardaway plays the part of the framed young man, while tour director Ira Tucker Jr. is the drug dealer who tricks him. Stevie’s own lawyer, Jonathan Vigoda, voices the judge who sends him away. It’s said that a Record Plant janitor is behind the famous line ordering the main character to “get in that cell”—a line that would later be sampled by Public Enemy on “Black Steel in the Hour of Chaos.”

At this point in the song, Wonder’s own voice undergoes a jarring transformation, from his sweet and smooth signature to the growl of a grizzled bluesman, as he spells out the bad news:

“His hair is long, his feet are hard and gritty/ He spends the life walking the streets of New York City/ He’s almost dead from breathing in air pollution”—notice the echo of Gaye there—he sings. Having once been excitedly “living for the city,” the man is now “living just enough for the city.”

It’s a gut punch and, four decades before the Black Lives Matter movement, a wake-up call attempt to show the world the brutality of being Black in America.

“I hope you hear inside my voice of sorrow/ And that it motivates you to make a better tomorrow/ This place is cruel, nowhere could be much colder/ If we don’t change, the world will soon be over/ Living just enough, stop giving just enough for the city,” Wonder ends it.

Musically, too, the song is miraculous. A thick slice of funk, soul and blues, it sounds like it’s created by an entire band and a whole group of background singers. But it’s all, save for the voices noted above, Wonder. That’s him on the piano, the drums, the Moog bass, the TONTO, the high and low harmonies, hell, even doing the handclaps—and, inevitably, influencing one Prince Rogers Nelson.

Stevie Wonder - Innervisions on Flipside TV (1973)

Reelblack One“He’s Misstra Know-It-All”

Wonder also speaks to the times on this pretty ballad which, despite the free-flowing “flute” sounds (actually the TONTO), is apparently a Watergate-era condemnation of disgraced President Richard Nixon: “He’s the man with a plan/ Got a counterfeit dollar in his hand/ He’s Misstra Know-It-All.”

The song presents a multi-verse character study of a Music Man-like con man who refuses to ever admit he’s wrong, even when presented with evidence.

“When you say that he’s livin’ wrong

He’ll tell you he knows he’s livin’ right

And you’d be a stronger man

If you took Misstra Know-It-All’s advice, ooh, ooh”

As Willie Weeks—the only musician besides Wonder on the song—lays down a slick bass groove and a butter-wouldn’t-melt gospel choir (actually all Wonder overdubs) croons, Wonder gets more forceful at the three-minute mark, layering on handclaps to emphasize the beat, half-beat and quarter-beat. Listen to what this is really about, he communicates without saying it.

In 1974, Wonder’s power-horn funk cut “You Haven’t Done Nothin’” (“But we are sick and tired of hearing your song/ Tellin’ how you are gonna change right from wrong”) would feel like a follow-up, complete with the Jackson 5 on backing vocals.

“All in Love Is Fair”

Much was going on in Wonder’s personal life too, as he documented the break-up of his two-year marriage to Syreeta Wright—a talented singer-songwriter in her own right who collaborated with Billy Preston and sang back-up on Wonder’s “Signed, Sealed, Delivered (I’m Yours).”

The Johnny Mathis-sounding ballad describes the failure of a relationship that never lived up to its promise in a series of clichés: “All is fair in love/ Love’s a crazy game … All of fate’s a chance/ It’s either good or bad/ I tossed my coin to say/ In love with me you’d say/ But all in war is so cold.”

Over the years, some have criticized that thematic choice, while others have argued that Wonder wrote it that way to prove, painfully, that the clichés are also truths.

While the song—which features Scott Edwards on bass—would later be covered by the suave likes of Shirley Bassey, Nancy Wilson and Dionne Warwick, it became a torchy signature for Barbra Streisand, who recorded it multiple times beginning with 1974′s The Way We Were.

“Higher Ground”

A joyous highlight of Innervisions, “Higher Ground” was also the album’s highest charting Billboard Hot 100 single, reaching No. 4.

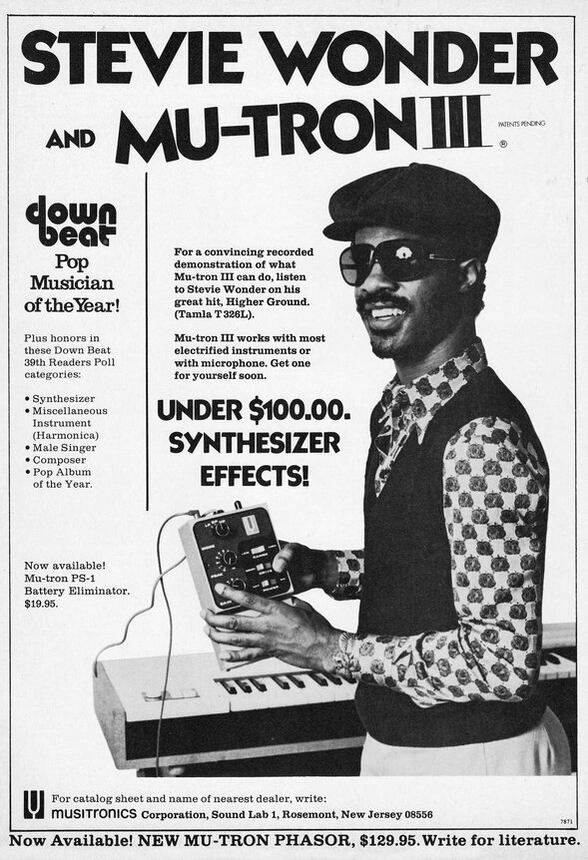

It seemed to come from divine intervention, as Wonder wrote and recorded the track in just three hours. This is another where he plays all the instruments, creating that unforgettable wah-wah clavinet sound by using a Mu-Tron III pedal and the funky bass via a Moog.

A party in a song, “Higher Ground” celebrates the idea of reincarnation: “I’m so darn glad/ He let me try it again/ ‘Cause my last time on Earth/ I lived a whole world of sin/ I’m so glad that I know more than I knew then/ Gonna keep on tryin’/ ‘Til I reach my highest ground.” (It also echoed Martin Luther King Jr.’s message of political transcendence and “call to higher ground.”)

But the lyrics took on much deeper meaning when, just days after the album was released, Wonder was a passenger in a car accident that involved a truck piled high with logs—one of which flew through the windshield of the car and into Wonder’s head, leaving him in a coma for four days.

The first sign of recovery came when tour director Ira Tucker (the same one who voiced the exploitative drug dealer on “Living for the City”) leaned into Wonder’s ear and began singing “Higher Ground.”

“His hand was resting on my arm and after a while his fingers started going in time with the song,” Tucker later recalled. “I said yeah! ‘Yeeeeaaah! This dude is going to make it!’”

Recovery was hard won, and Wonder later said he didn’t think the accident was an accident. As Wonder—who lost his sight shortly after birth—told The New York Times, the experience “opened my ears up to so many things around me.”

He also told the paper how, while “Higher Ground” was written before the wreck, “something must have been telling me that something was going to happen to make me aware of a lot of things and to get myself together. This is like my second chance for life, to do something or to do more, and to value the fact that I am alive.”

In 1989, Red Hot Chili Peppers created a memorable pop culture moment of their own with a slap-bass cover of “Higher Ground.”

“Don’t You Worry ‘bout a Thing”

Likewise, Latin-inflected “Don’t You Worry ‘bout a Thing” put out a positive message—a 1973 version of accentuating the positive.

“Don’t you worry ‘bout a thing, mama,” Wonder promises. “’Cause I’ll be standing on the side/ When you check it out.”

It starts off with spirited, playful mambo piano and a melody that recalled Horace Silver’s “Song for My Father,” as Wonder showily crows and tries to impress a woman with talk of having been to Paris, “Iraq, Iran, Eurasia” and telling her he speaks “very fluent Spanish”: “Todo ‘stá bien chévere,” he coos—basically, everything’s really great—before she corrects his pronunciation.

Stevie’s piano, its rhythm borrowed from Tito Puente’s “Ran Kan Kan” (as pointed out by Steve Lodder in Stevie Wonder: A Musical Guide to the Classic Albums), is a marvel here, as are the bongos from Sheila Wilkerson.