On the evening of September 13, 1963, at the closing concert of the Gaudeamus Festival, an odd instrumentarium occupies the lobby in the Dutch city of Hilversum’s town hall. Ten performers dressed in tailcoats, faces emotionless, go onstage in single file and place themselves on either side of tables, where a hundred or so pendulum metronomes are carefully lined up. The conductor makes his entrance a few seconds later. After several minutes of absolute silence, he outlines an arm gesture. Just then, the ten performers put into action the metronomes, preset to different speeds, before leaving the stage just as seriously as they came. The audience members watch half-dumbstruck, half-bemused, as for about ten minutes, a cacophony of disorderly clicks fills the room, and then progressively diminishes until the last metronome, the slowest, finishes. The audience had just witnessed the world premier of the “Symphonic Poem” of György Ligeti, the remarkable composer from the Eastern bloc who had been titillating the avant-garde sphere since his arrival in Vienna four years prior.

György Ligeti - Poème Symphonique (WP/ Holland 1963)

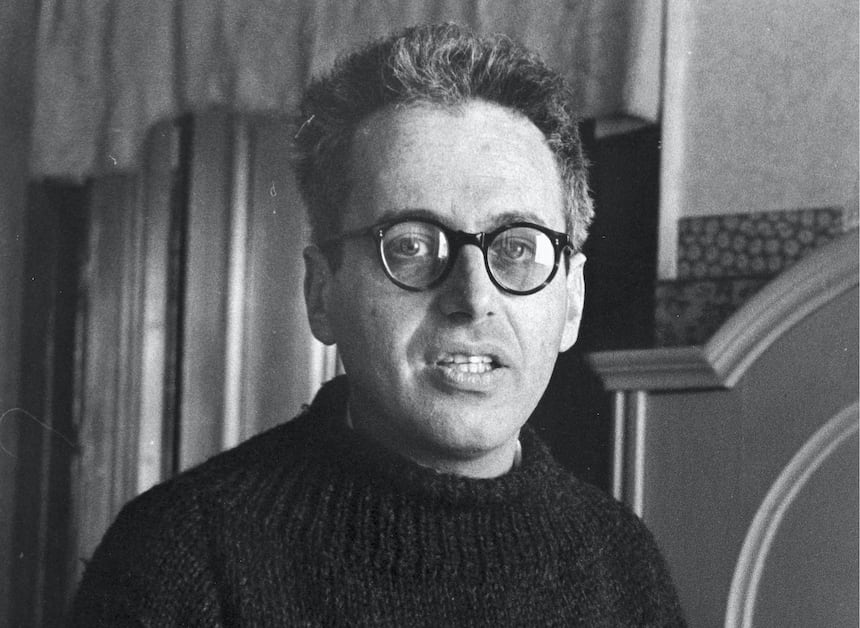

LeCapIt was not Ligeti’s first provocative act. He fled his native Transylvania, precisely because Soviet authorities looked down upon his free-thinking spirit. His musical experimentations didn’t match up with the aesthetic canon of Socialist realism. From the very beginning, Ligeti had been haunted by obsessions that not even the trauma of the Holocaust and exile managed to quiet; rather, as time went on, the composer would turn his wounds into his strength and, dare we say, his style.

To understand, one has to look back to his childhood. György Ligeti was born in 1923 in Romania, in the village of Dicsőszentmárton (present-day Târnăveni). His parents, Ilona and Sandor Ligeti, were music-lovers, albeit not musicians themselves. His father, a bank employee, was an amateur writer, an author of social science fiction novels, which he wrote on a typewriter in his free time. The young György would fall asleep to the sound of this machine, from that point on having a strong taste for automatons and mechanical systems – to which “Symphonic Poem” for 100 metronomes is a testament. A liking encouraged, or rather provoked, by his father, who pressured his son to pursue a scientific career, believing it to be his destiny. But the politics of the country decided otherwise. Born to a Jewish family, György Ligeti was subjected to the first anti-Semitic laws, notably a number of clauses that drastically limited the admission of Jews to universities. Seeing his dreams of higher education evaporate before his eyes, Ligeti enrolled in the municipal conservatory of Cluj upon finishing secondary school in 1941; a default choice that turned out to be the right one. At the time, the family rented a piano that György would often play with his brother, a brilliant violinist. However, the war would cause this fraternal bond to come to a tragic end: György would lose his brother and his father in 1945 when they were deported and assassinated in the concentration camp of Mauthausen.

After the war, with nothing keeping him in Cluj any longer, two choices presented themselves: Budapest or Bucharest. “I chose Budapest because I wanted to meet Bartók, or at least to meet those around him, the intellectual circle he was in. He was my idol, the idol of an entire young generation of aspiring composers like myself, because he represented both Hungarian music AND modern music”, explained the composer. In September of 1945, newly enrolled at the Franz Liszt Academy of Budapest, Ligeti found the building encircled by black flags at half-staff: the news of Bartók’s death had just broken. This became a symbolic mourning for the young student, who interpreted it as encouragement to make a musical footprint of his own. At the Liszt Academy, he pursued an education that was “traditional, very strict, but very good”, but it was also a period of great cultural freedom in the country, where the works forbidden during the Nazi occupation were newly authorized.

This respite, however, was short-lived, as in August of 1949 the country was declared The Hungarian People’s Republic, after the Soviet model. Ligeti very quickly picked up on the dawn of a totalitarian regime and refused to affiliate himself with the party. Just as the Nazis did, the Communist authorities imposed their own aesthetic canon. Ligeti, who had since become a teacher, paid the price when he received a warning for daring to have his students study a score by Igor Stravinsky. His work as a composer was also threatened: “Folklore was only authorized if it was politically correct. Put simply, if the minor/major harmonies were seen as acceptable, Eastern modalism was tolerated, but the harmonic style played by village ensembles, whose playing abounded with dissonances and ‘dirty’ notes, was rejected outright. The fourth movement of my Concert Românesc (1951) includes a passage in which an F-sharp major appears in the context of an F major. The cultural apparatchiks needed no more than that to ban the work. As a reaction to this ideological surveillance, I thus decided to develop a musical style that was radically chromatic and dissonant.”

For Ligeti, who had seen dictatorship decimate his family and bridle his creativity, artistic freedom became vital and non-negotiable. Increasingly threatened, he fled the country in the fall of 1956 during the insurrection of Budapest, bringing with him nothing but “his toothbrush and the manuscript for his first string quartet: I wanted to have something to show for myself once I made it to the West!” He was first led toward Cologne, invited by Karlheinz Stockhausen, who had established his research and recording studio there. He also enjoyed a certain reputation following the creation of the “Gesang der Jünglinge”, now considered to be the first electroacoustic work of all time. It was in this studio that Ligeti composed “Artikulation” (1958), a hallucinatory and futurist sound experiment, which Rainer Wehinger would build upon twelve years later, adding a graphic score resembling the Bauhaus paintings of Kandinsky.

Ligeti - Artikulation

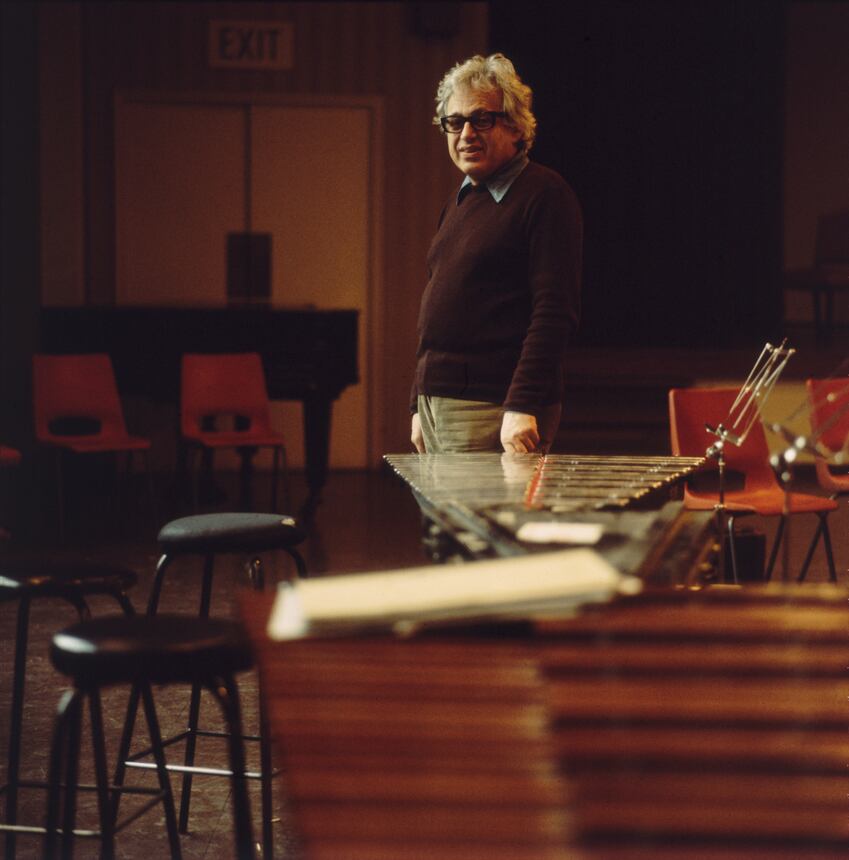

Donald CraigStill guided by his old obsessions and independent spirit, Ligeti didn’t stay in Germany for long, and settled into Vienna, Austria in 1959, where he resided until his death: “I quickly abandoned the work in the studio because I didn’t like the sonorities the machines made. But this experience was greatly beneficial to me because I was able to incorporate the method into writing for orchestra. This led to Atmosphères in 1961.” “Atmosphères” is the enhanced version of a now-lost piece from 1956 entitled “Visions”: “I look back and see myself walking alone along the streets of Budapest, with a strong acoustic image in mind: that of music that is completely static, with neither beginning nor ending.” The search for music suspended outside of all temporality was a quest that Ligeti would pursue throughout his career, and a motif that is found in a number of his later works such as Lux Aeterna, Lontano, Ramifications, and even certain studies for piano.

Another feature of his work is its relationship to death; sometimes anxiety-ridden, at other times mocking, always ambiguous. Behind the often anxiety-provoking appearance of his atonal compositions, there often hides a sense of humor that is sarcastic and full of vitality, for instance in, Requiem (1963 - 1965) or his opera Le Grand Macabre (1978): “Fear of death is a feeling that follows me around at all times, the paintings of Bosch and Bruegel made a strong impression on me when I was a child. It was a source of inspiration. But my music hides something else, an impulse to live: my revolt against the Nazis and against communism. There is a dark and aggressive mood within me at all times, which I don’t show and which I conceal with humor and kindness, perhaps as a reaction to all that I’ve been through.”

In 1968, Ligeti became known to the general public when Stanley Kubrick used three of his compositions – “Atmosphères”, Requiem, and “Lux Aeterna” – for 2001: A Space Odyssey, which went on to become a cult classic. Without having been consulted beforehand, Ligeti considered taking legal action for some time, before coming to an amicable agreement proposed by Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer - a happy ending that would allow Kubrick to use other Ligeti works in his films: Lontano in The Shining, and Musica Ricercata in Eyes Wide Shut. Even today, these films remain inseparable from their soundtracks in the minds of cinephiles. Although the two men never met in person, their mutual admiration is well-known. At the time of Kubrick’s death in 1999, Ligeti wrote a moving letter to his executive producer Jan Harlan in which he declared: “[Kubrick] was just as meticulous as I am. I would have liked him as a professional, and a beast, not unlike myself.”

From the 1980s, Ligeti explored in greater depth the technical variables of composition and the search for virtuosity: “Virtuosity is very important to me, because it entails an element of danger that requires you to go to the limits of what’s possible.” Études, compiled into three books composed between 1985 and 2001, falls into this category of difficult pieces. Pianist Pierre-Laurent Aimard remembers a recital when the composer, present in the room, came to give him a reminder: “Before performing, I asked him if the tempo of the étude Zauberlehrling, which he had asked me to speed up, was finally right. His response was yes. ‘But,’ he added, ‘now, play it again, but even faster.’ He thrived off of the risks that his performers took on stage, every single time. Moreover, this risk-taking is inherent to a great number of his compositions, oftentimes in an extreme, even unsettling way.” Viola player Tabea Zimmermann, for whom “Viola Solo” (1994) was created, recounts having told Ligeti’s assistant, a few weeks prior to the first performance, that she had never played anything so difficult, to which the woman responded: “Tell György, he’ll love that!”

Until his death in 2006, Ligeti carved his own stylistic path relentlessly and without compromise, building a body of work that is at once restless and fiery, pessimistic and luminous, and in which grimaces are transformed into laughter. He afforded himself the luxury to walk around with his immense curiosity slung over his shoulder, without ever pigeonholing himself into a school, or appropriating the great influences of his time: musique concrète with “Artikulation”, hommage to minimalists Steve Reich and Terry Riley in Three pieces for two pianos (1976), serial music with Musica Ricercata (1951 - 1953)...Yet this eclecticism goes far beyond the scope of contemporary music alone! He showed great enthusiasm when one of his students introduced him to Michael Jackson’s “Billie Jean”, declared his love for the jazz of Thelonious Monk and Bill Evans, and drew from the music of Africa and the Caribbean, introduced to him by composer Roberto Sierra – this latter discovery strongly influencing his compositions from the 1980s onward, particularly his Études.

“I don’t have a dogma. I’m always looking for new possibilities.”

Ligeti possessed a flexible ear and a staggeringly inventive creative approach that he summarized in the following way: “I have a somewhat general idea, a sort of vision of what I want to do musically. But I don’t have a system for writing. I never know what I’m going to compose after the piece that I’m presently composing. I don’t have a dogma. I’m always looking for new possibilities.” This acceptance of the unexpected, this humble and methodical uncertainty about the future, is what Ligeti brings out in a complex and bountiful body of work that continues, more than 15 years after his passing, to greatly fascinate us with its ambiguous light and shade.