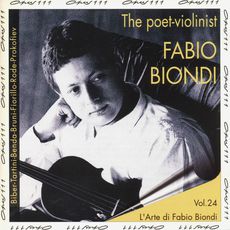

Palermo-born Fabio Biondi, who displayed a gift for the violin from an early age, grew up in a family of Sicilian music lovers, immersed in the austere music of Palestrina which his father played all day long. His grandfather, a lawyer and a good amateur pianist, was a friend of the composer Ruggero Leoncavallo. As a unique, rebellious twelve-year-old, Fabio Biondi was already part of the RAI’s (the Italian radio and television company) I Giovani Cameristi ensemble. He was twenty when he founded the Stendhal quartet with three friends who, like him, were enamoured with both baroque music and the American minimalists (Terry Riley, Steve Reich, Philip Glass) - quite a contrast that would lay the foundations for a particularly audacious programme.

Fabio Biondi quickly moved on to the Baroque violin and became a much sought-after musician, at a time when new ensembles were popping up everywhere. This is how he became a violin soloist for groups as renowned as Philippe Herreweghe’s La Chapelle Royale, Marc Minkowski’s Les Musiciens du Louvre, Jordi Savall’s Hespèrion XX, and Gérard Lesne’s Il Seminario musicale, amongst others.

Keen to show that being a Baroque specialist is not a limited musician or a repertorial outcast, Biondi plays all sorts of repertoires, including Prokofiev, of whom he is especially fond. Now also a conductor, he leads both his ensemble Europa Galante, and modern orchestras, providing them with the articulations and techniques needed to play Baroque or classical pieces correctly for today's ears.

We have recently seen Fabio Biondi (January-February 2020) heading the Orchestre de la Suisse romande in the pit at the Grand Théatre de Genève. On this occasion, he conducted Mozart’s The Abduction from Seraglio for the first time. It was a highly controversial version, for which the libretto was entirely rewritten in French by Turkish poet Asli Erdogan - in order to tell her own story - with stage direction by Luk Perceval. Although it had little to do with the original piece, it was an opportunity for Biondi to break free from the rigidity of the opera through a radical rereading that evoked eighteenth-century production methods, according to which pretty much anything goes.

'There’s nothing more unbearable for me’, he once said, ‘than categorisations that fence in all life. The Baroque movement’s mistake was imposing authenticity rules. What is authenticity? Looking for other, more original behaviours and ways of playing in the manuscripts is essential, but so is escaping our constraints. The “historically informed” attitude is the best definition in my opinion, as it implies that we know where we come from in order to know where we’re going. It’s a living movement. It’s not just about playing short, clipped notes for early music and long, vibrato notes for Romantic pieces’.

Though he plays several old Italian instruments, the violinist uses metal strings and a modern bow copied from a period piece in his collection. Asked about this, he is pragmatic: ‘You need to be able to mix things up to find what you are looking for. “Period instrument” means nothing: how they were built changed every twenty years and differed by region. The angles, the tension, the shape of the bridge were all different in Italy, in France, and in Germany. As for the 415 Hz tuning fork, that’s total nonsense. The same applies in this case. In England in 1724, it was 420. In Venice or Naples it was 440, 407 in Rome, then in France, Jean-Marie Leclair used a 408 Hz fork’.

Create a free account to keep reading