Jazz

At the end of 1957, when rock'n'roll was sweeping America and he was one of its masters, Ray Charles played at Carnegie Hall on the same bill as Dizzy Gillespie, Chet Baker, Thelonious Monk, Sonny Rollins, Billie Holiday and John Coltrane. In 1960, he toured with Art Blakey, Horace Silver and Dinah Washington. And ten years later, he accompanied two historic jazz figures, Louis Armstrong and Duke Ellington, on stage at Madison Square Garden. Certainly, Ray Charles was not just a popular singer with foot-tapping, sing-along hits. He was first and foremost a jazzman, a pianist trained as a child in music theory, then in classical music and then in jazz. And he also played saxophone. Ray Charles comes from an era (the 30s and 40s) when jazz was the most popular music, which could be found everywhere: on the radio, in the cinema, in cocktail bars or in large venues. Being able to play jazz meant being able to play everything. That might sum up Ray Charles, who always returned to jazz, or maybe never really left it. In 1956, after proving himself as a rhythm'n'blues singer, Ray Charles recorded two instrumental albums of cool and bebop jazz for Atlantic, including Soul Brothers with vibraphonist Milt Jackson. Although his music was rooted in the tradition of big bands and jazz singing, Ray Charles was at the cutting edge of modernity: in the early 1960s, he recorded the explosive Genius + Soul = Jazz on an electric organ, with musicians from Count Basie's orchestra and his friend Quincy Jones as arranger. This high-end album was his second release with a label that would become a legendary part of the history of free jazz: Impulse! In this splendid period, Ray Charles also reached new heights as a jazz crooner, notably on a whole album of marvellously languid duets with the singer Betty Carter.

Country

As a boy, Ray Charles was only allowed to stay up late one night a week: Saturday, to listen to the Grand Ole Opry on the radio. Broadcast from Nashville by WSM radio, the Grand Ole Opry was the voice of country music in America. This music, white blues that black people also listened to and loved, united the USA just as much as did its constitution. In the late 1950s, having become a star with the very gospel What'd I Say, Ray Charles fulfilled his dream of recording country songs, starting with a cover of Hank Snow's I'm Movin' On, which was to be his last single for the Atlantic label. This was a great moment in his discography: the melody, the railroad rhythm and the pedal-steel are typical of country music, but Ray Charles starts the song with horns and ends up introducing it to The Raelettes and the atmosphere of black churches. Three years later, on his new ABC label, Ray Charles returned to full-length country music with the two volumes of covers Modern Sounds In Country And Western. In these records, Ray Charles does not go country so much as he marinates country in his big-band sauce, with string and brass arrangements that sound richer than ever. Compositions, stories and emotions are more important than form. Later, Ray Charles would sing with the country giants Johnny Cash and Willie Nelson. At Ray Charles' funeral in 2004, Willie Nelson sang a moving Georgia On My Mind, a Hoagy Carmichael song that always brings people together.

Rock’n’roll

In 1957, the label Atlantic released Ray Charles' first album (a compilation of singles) in its 'Rock'n'roll' series - an opportunistic marketing idea to sell its rhythm'n'blues artists (Ruth Brown, The Drifters, Joe Turner, etc.) to the rock audience. The same label would later try to sell Ray Charles under the label "twist"... But Ray Charles was not strictly speaking a rocker. He was too sedentary, too blind, too musical, too sophisticated. He has the same popular musical roots as the first rockers (blues, gospel, country) but is also immersed in the world of jazz, that "adult" music which requires the musician to have real technical skills and is not specifically aimed at teenagers. The teenagers of the late 50s and 60s, both black and white, were not averse to dancing to Ray Charles' songs. And the pioneers of rock were to make history very early on, covering his songs: Eddie Cochran with 'Hallelujah I Love Her So', Elvis with 'I Got A Woman', The Everly Brothers with 'This Little Girl Of Mine', Jerry Lee Lewis with 'What'd I Say'... A contemporary of the early years of rock, Ray Charles was an influence on it more than a participant. In the early 1960s, French rockers and yéyés adapted his songs en masse, and future English rock stars cut their teeth on them, such as The Animals ('Talkin' About You') or The Beatles, who saw the light in 'What'd I Say' and covered 'I Got A Woman' on stage in Hamburg clubs. Ray Charles returned the favour by covering 'Yesterday' and 'Eleanor Rigby'.

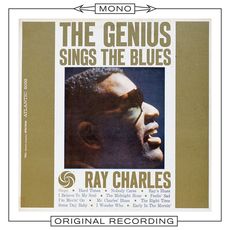

Blues

In the liner notes of his first records, Ray Charles is described as a blues singer. This was reductive even at the time, but nevertheless it was not wrong. Ray Charles of course grew up in the context of the blues: the South, poverty, blindness. His eclectic tastes and upbringing - few bluesmen studied Bach and Mozart as children - freed him from cleaving too closely to the narrow path of a blues musician. Before making records under his own name, Ray Charles was a second-in-command to well-known blues musicians, including guitarists Lowell Fulson and Guitar Slim. Their electric style can be heard in some of Ray Charles' songs, such as 'Black Jack' and 'Sinner's Prayer'. Ray Charles' blues is sometimes slow and heavy, but more often it is rhythmic and sensual, in the Californian style of his model Charles Brown, or in the style of New Orleans, the city where he lived, played and recorded, and where he mastered the art of the musical cocktail. 'Mess Around', his first hit, sounds like an exuberant New Orleans rhythm'n'blues classic.

Gospel

Like any self-respecting old-school African-American musician, Ray Charles grew up with faith and in churches. As a child, he sang there. There are few purely religious songs in his long discography, but there is gospel in all his records: in the depth and freedom of his singing, in the choruses of The Raelettes, in the sound of his voice, in his rhythms, in the mixture of lament and joy he expresses. Ray Charles made no secret of it in an interview: he wrote his first songs by adapting gospel hymns, replacing the worship of Jesus with worship of a sweetheart. His huge 1956 hit ‘Hallelujah I Love Her So’ is a note-for-note copy of the single ‘That’s Why I Love Him So’, released three years earlier by the Gospel All Stars. Ray Charles was enough of a genius to recycle a gospel song into a love song, while including the religious term “hallelujah” in its title. The same goes for ‘It Must Be Jesus’ by The Southern Tones, which became ‘I Got A Woman’ in the hands of Ray Charles. The classic ‘What’d I Say’, considered the template for soul music, was born out of a stage improvisation with The Raelettes before being recorded in the studio, and is another perfect example of unbridled, defrocked gospel he made. All the ingredients of religious fervour can be found there, but in a very sexualised context. Despite the scandal at the time, Ray Charles did not in fact commit blasphemy. Music was his only religion, and he was most ecumenical.