The mastermind of the group, RZA, once said the Wu-Tang Clan were “a strange mixture of ex-felons, self-taught men, tough guys, fashion guys, as well as deep thinkers.” So how did a group of eight barely twenty-something rappers, hailing from some of the poorest neighborhoods in Staten Island and Brooklyn, manage to take the rap world by surprise with a first album that had such a low budget and convoluted aesthetic?

“RZA definitely had the idea of Wu-Tang by 1991″, GZA told Brian Coleman in the book Check the Technique. Yet it was as early as 1987 that the man otherwise known by his government name Robert Diggs was passing the mic to MCs – several of whom would go onto become members of the Wu-Tang Clan – in his home studio in Stapleton, northeast Staten Island, New York, where he’d settled down after growing up in Brooklyn and living in North Carolina, Ohio, and Pittsburgh.

In 1990, his cousin Gary E. Grice, three years his senior, who was yet to take on the name GZA, signed with the label Cold Chillin’, which had already launched the careers of MC Shan, Biz Markie, and Big Daddy Kane, forerunners of the period between 1987 and 1990. Under the name The Genius, he released a first album, Words from the Genius, produced for the most part by Easy Mo Bee, who had just created several tracks for Big Daddy Kane and would go onto produce “Party and Bullshit”, the first single of none other than the Notorious B.I.G.. As for RZA, he signed a contract with Tommy Boy at the same time, for a single that became the simple and easygoing “Ooh, I Love You, Rakeem”, released under the name Prince Rakeem. Yet Cold Chillin’ hardly made an effort to promote its new aspiring star and Tommy Boy opted out of making an album (the label also wouldn’t pay bail for RZA upon his incarceration in Ohio). That was enough to lead the two cousins to set up shop themselves, forming the trio All In Together with a third member known as Ol’ Dirty Bastard. RZA, who began to produce his own beats and freestyle with Dennis Coles aka Ghostface Killah, his roommate with a checkered past, would bring together his cousins, along with the MCs Inspectah Deck, U-God, Raekwon, and Method Man, as if enlisting the city’s best thieves for the heist of the century.

The story is well-known: it was in his apartment at 134 Morningstar Road – that is, far from the cities of Stapleton and Park Hill where these hungry artists began – that the charismatic and determined RZA would convince his accomplices to let him take their destiny in hand and commit body and soul to the venture that was Wu-Tang, at least for the next five years. “I used the bus as an analogy,” he recounts. “I said, ‘I want all of y’all to get on this bus. And be passengers. And I’m the driver. And nobody can ask me where we going. I’m taking us to No. 1. Give me five years, and I promise that I’ll get us there.’”

“Protect Ya Neck”, the founding single for Wu-Tang, which was nearly complete by 1992 (Masta Killa, GZA’s disciple, would join the group later on), is an assault like rap had rarely endured before.

Yoram Vazan, owner of the Brooklyn studio Firehouse, where the sessions for Enter the Wu-Tang took place, remembers the musical explosion: “They played me “Protect Ya Neck” and it was very hard and incredible and it never stopped hitting you, you know?” It must be said that this sequence of verses, each just as incisive and arresting as the others, is no less than amazing, with styles and punchlines colliding on a production unhindered by any embellishment. The extraordinary energy and urgency that emanates from the track is astonishing. It’s a declaration of war and a parade of its soldiers. More than a quarter of a century later, the suicidal choice to launch the group’s career with a such a radical posse cut, that even lacks a chorus, seems like a stroke of genius.

DJs Kid Capri and Funkmaster Flex performed the track, recorded on a self-produced album, at their respective shows, and the labels unsurprisingly came knocking. Yet RZA turned out to be a seasoned businessman, taught quickly and effectively by his previous experience being shortchanged by record labels. He managed to get Loud Records, who ended up with the winning bid, to let each member of Wu-Tang sign with the label of their choice. An official version of “Protect Ya Neck” was re-released, with the logo of Steve Rifkind’s label, distributed under the RCA umbrella, replacing RZA’s telephone number and with the solo “Method Man” as the B-side.

The group’s members crowded into a cramped studio, pushed by RZA’s vision to tinker with rudimentary machines (with the exception of a brand-spanking new Ensoniq EPS sampler that let him manipulate sources as if playing notes on a keyboard), extracting and assembling dialogues from obscure films (directly from a video recorder), lines of swinging jazz piano, and fragments of goth soul or haunting blues. The MCs gave their all in unbridled battles, and from there the producer got stuck into splitting and interchanging verses and reprogramming the beat once the vocals were laid down, while always retaining their essence.

From the mundane tales of everyday life in the Staten Island projects – the least-populated borough of New York, which for a long time had been treated like a public junkyard for the rest of the city – the Clan grafted an entire mythology and phraseology, inspired by the existence of Shaolin Buddhist monks, as well as references to chess, math, the mafia, and the precepts of the Nation of Islam. The result is a street rap that’s baroque and elevated, incarnated by personalities varying from the whimsical Ol’ Dirty Bastard, to the dark and complex GZA, to the virtuosic Method Man. All performers with staggering charisma, their life experience bleeds through every phrase they spit into the mic (most of the group’s members have gone to prison and grew up without the presence of a father figure). Everything contributes to the album’s unique atmosphere, at once menacing, erudite, mystical, and cheeky: the interludes where the members of the Clan chat like mobsters (on topics as diverse as torture devices or Hong Kongese action movies), the vocal samples from records that RZA painstakingly selected (the Stax classic “After Laughter (Come Tears)” by Wendy Rene on “Tearz,” for example), and the unique lo-fi texture that comes out of such an unorthodox use of the sampler.

Wu-Tang Clan - C.R.E.A.M. (Official HD Video)

WuTangClanVEVOAlthough the athletic and egocentric “Method Man” and “Wu-Tang Clan Ain’t Nuthing to Fuck Wit” act as the bangers necessary on any good rap album, it’s the soulful ballad “Can It Be All So Simple” and the nihilistic masterpiece “C.R.E.A.M.” (which samples the soul trio produced by Issac Hayes, The Charmels) that are the most fascinating.

Touchstone of New York hardcore rap, 36 Chambers is an aggressive and mystical response to the intentionally hedonistic and sunny California G-funk of Dr. Dre and Snoop Dogg, who dominated the rap world at the time: in the fall of 1993, Dr. Dre’s The Chronic, released at the end of 1992, had just begun to fall out of the Billboard Top 10, and Doggystyle, Snoop Dogg’s debut, was fresh out of the oven.

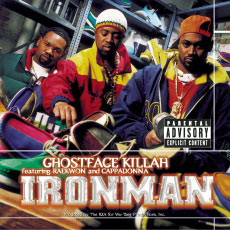

The album allowed for RZA to surpass the status and influence of his teachers in production, Marley Marl, Prince Paul, and Large Professor, and for the rappers of the Clan to launch solo careers that would be crowned with success. The prophecy came to fruition and RZA succeeded in sending Wu-Tang into orbit in the space of five years. Between the releases of Enter the Wu-Tang and the double album Wu-Tang Forever, a huge commercial success in 1997, the five main rappers gave the world their own solo albums. Method Man was signed by Def Jam for a record breaking amount of money and came out with the classic Tical. Ol’ Dirty Bastard split off as early as 1995 with Return to the 36 Chambers under the label Elektra. Liquid Swords, GZA’s masterpiece, was released on Geffen. Ghostface Killah became Ironman under the label, Epic. And Raekwon chose to trust Loud’s Steve Rifkin for his Only Built 4 Cuban Linx. All of these albums, which were each milestones for modern rap, were produced and piloted by RZA in a state of grace, who, to say the least, sailed his boat to port.

25 years later, Wu-Tang reunited (with the exception of Ol’ Dirty Bastard who passed away in 2004, but with the addition of long-time collaborator Cappadonna) in front of Sacha Jenkins’s camera for the documentary series Of Mics and Men. The band has become legendary, generating more literature and commentary than any other rap group (the English writer Will Ashon’s brilliant Chamber Music being particularly noteworthy). RZA himself has published two books , the highly-regarded Wu-Tang Manual published in 2005 and The Tao of Wu in 2009, which led to the 2019 fiction film Wu Tang: An American Saga, produced and distributed by Hulu, with Ashton Sanders in the role of RZA.

![Enter The Wu-Tang (36 Chambers) [Expanded Edition] - Wu-Tang Clan Enter The Wu-Tang (36 Chambers) [Expanded Edition]](https://static.qobuz.com/images/covers/17/00/0888880400017_600.jpg)