The Best of Creedence Clearwater Revival compilations are often double albums. This band has made so many hits and memorable songs that it’s impossible to fit them all on a single record. Between 1968 and 1972, having been around for five years, Creedence Clearwater Revival released seven albums, had a dozen songs on the international charts, and managed to sell more records than The Beatles. Creedence followed on as the spiritual successors of The Beatles in the rock timeline, satisfying the band’s leader, John Fogerty’s, lifelong dream to be as well-known and respected as the Fab Four. He also dreamed of returning to the founding myths of American rock; the blues and rock’n’roll of the 50′s.

The members of Creedence Clearwater Revival were perfect anti-rock stars, who never became poster boys or generational icons. Their rootsy, funky songs, however, took on a life of their own, surviving beyond their creators and remaining relevant throughout the many shifts in popular music over the years, eventually cementing themselves in our collective memory. Born on the Bayou, Green River, Susie Q, Lodi, Bad Moon Rising, Feelin’ Blue, Fortunate Son, The Midnight Special: all these songs, and many more, are enchanting pop rituals of possession that take the listener (the biggest fanatic) on a journey, with a couple Beatles albums in the car radio, through Creedence’s dreams of the American South; between the bayous of Louisiana and up to the Sun studios in Memphis, all the way to Chicago’s black neighbourhoods.

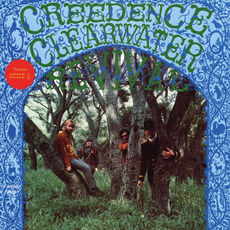

This music is an illusion. The ultimate band of Southern syncretism, Creedence had never stepped foot in the South when they recorded their first songs, although they had dreamed about it a lot, taking the time to refine their imaginary expedition. By 1968, the year the first album was released, the band members had already been making music together for almost ten years in the suburbs of San Francisco. They first played under the name Blue Velvets, and then as the Golliwogs for some time after that. On the Golliwogs’ recordings, one hears an honest garage band sounding like any one of the thousands of other Beatles derived wannabes of the time. How, then, did these Golliwogs become the unique Creedence Clearwater Revival, authors of a debut album that would go down in history, containing the first of countless hits, just a few months later? They did so, first of all, by changing their name. Creedence was chosen after the first name of a friend of John Fogerty. The word “credence” also means “belief” or “faith”. Creedence is a dense word that sounds good and dances on the tongue. The word Clearwater was taken from a beer advert as it brings to mind a fresh and unpolluted spring. Revival was chosen to signify the rebirth of the band after the Golliwogs, with a religious connotation that refers to the rituals of the Evangelical Baptist church. Therefore, Creedence Clearwater Revival, meaning “the rebirth of the clean water of faith”, doesn’t really mean anything precisely (not like Rolling Stones or Velvet Underground) but it leaves open many avenues for interpretation, especially with regards to their past. As you may recall, Creedence first came together in the late 50′s. Reinvigorated by the fresh rebrand, John Fogerty felt he could steer his band to reclaim that golden age of Sun Records’s original rock’n roll and Chess’ electric blues.

Creedence Clearwater Revival - San Francisco 1970

propylaen2001The first track on the first album is a programmatic cover: I Put a Spell on You by the fantastic Screamin’ Jay Hawkins. He was one of the first of rock’s puppets to conjure up voodoo symbolism, and especially to fantasise about it, since he wasn’t born in New Orleans but much further north, in Cleveland, Ohio. While his original 1956 release was frankly comical, Creedence’s version is troubled and sombre, with long acid guitar tracks (the first verse is a guitar solo of almost two minutes), from which John Fogerty’s tormented voice emerges. This excellent debut in the band’s discography led to what is regarded as the album’s pinnacle, and Creedence’s first hit; Suzie Q. It was another cover of the 50′s bluesy rock’n roll classic Susie Q by Dale Hawkins, which the Stones had also covered fantastically four years earlier. But Creedence took it elsewhere, further, dragging the original down into a psychedelic swamp, swirling hypnotically, where the guitars advance relentlessly, just held back from the brink of combustion by the constance of a haunting, almost krautrock, rhythm. 1968 was a symbolic year in the period (the second half of the ‘60s) where visible or underground musical revolutions burst through, stirred up everywhere by the invincible Beatles, Hendrix, Velvet Underground, Dr John, the Stooges, and Captain Beefheart, to name just a few from a very long list. Throughout the 8 minutes of Suzie Q, one senses the overarching atmosphere within which music was created during those years, against the background of the Vietnam war and of the hippie revolution.

Creedence could have capitalised on this inspiration in the psychedelic zeitgeist. Yet, following Fogerty’s sepia-toned black-and-white vision, the band decided to take a different path, going deeper into the bayou, the neo-rural, the tradition and the simple (at least in appearance); the roots. If their hippie contemporaries in San Francisco embodied counterculture, Creedence represented a counter, counterculture. A return to culture, which even came close to agriculture. A faith in tradition almost radical in its honesty. Harvest time came for the band that had planted its first seeds ten years earlier and toiled them restlessly; it was, and continues to be, bountiful.

Stronger than The Beatles

In 1969, Creedence Clearwater Revival released no less than three albums (Bayou Country, Green River and Willy and the Poor Boys), all excellent and filled with songs that have stood the test of time. These albums formed a homogeneous trilogy, a Holy Trinity even. Songs from one could appear on the other and vice versa. There isn’t a great sound or stylistic evolution between the three – the third one is perhaps a touch more rootsy than the other two.

In January 1969, the band made a splash with the simultaneous release of Bayou Country and the single Born on the Bayou/Proud Mary. These two songs, like the rest of the album, established the Creedence style; an exhilarating alchemical fusion of roots rock, soul and country. As the band proclaimed its passion for the American South, it left behind the influence of California and psychedelia. If Creedence is to be considered, both musically and in its image (the working-class combo of jeans and checked shirts), against the current of its time, this reaction is rather healthy and well conducted. With each riff, their songs proclaim “it was better before”, without it smacking of lazy fundamentalism or out of touch, museum age wrinkly rock. They champion a timeless sound that is every bit as viable now, ensuring they will always be there to lead the way for future generations of alternative country and roots rock musicians.

Creedence’s artistic philosophy is contained in the title of the fourth song from Green River, their second album for 1969 – when Creedence sold more records than the Beatles. It was called Wrote a Song for Everyone, and that says it all. John Fogerty doesn’t write songs for hipsters or hippies. He writes and sings for everyone, everyday listeners and rock fanatics, city dwellers and country folk, students and workers, those enlisted for Vietnam and those who didn’t want the war. It is listened to in America and all over the world, and has been from 1969 until today. Everyone knows Creedence’s songs and loves them. Like Chuck Berry or Otis Redding, they are part of a cultural landscape that goes beyond them.

The only people who remained to be impressed were the hippies at Woodstock in 1969. On the 17th of August, Creedence performed in front of an audience whose patience and critical faculties had been partially scrambled by a Grateful Dead set that overstayed its welcome, and a non-negligeable indulgence in Woodstock’s famously cannabis-based refreshments. John Fogerty retains a certain bitterness about the lukewarm reception. The recording of the concert, released in 2019, vindicates his feelings by showing that Creedence’s songs play as well on stage as they do on the radio.

The end of Fogerty’s rein

On the cover of Willy and the Poorboys, the third and final album for 1969, the picture shows the band playing in the street for some Black children. A group of buskers in a jug band style arrangement, with some acoustic instruments, attempting to reconnect with the music of a time before electric amplification and recording studios. As the band was at the height of its commercial and artistic success, this image was of course an illusion, but it was a beautiful one. The members of Creedence aren’t really street musicians, but their ambition was always to bring rock and pop back to the streets, grounding it for everyone. From the public’s point of view, Creedence’s members are stars. But they are far more likely to be seen piled into a rickety pickup truck than in the cushy backseat of a Rolls Royce. Very high class, for the middle class. Willy and the Poor Boys is perhaps the band’s best album, accentuating the contrast between very folksy tracks and others that are much more electric.

The release of Cosmos Factory in July 1970 marks a notable change in the band’s image and style. For the first time, the album cover photos show the band indoors (in their rehearsal room), not mingling with nature outdoors as they usually are. It is a wonderful succession of memorable songs, joining the band’s already numerous classics. In fact, it managed to be even more successful than the albums from the previous year. Yet, it may have also heralded the beginning of the end. However, the very long psychedelic cover of I Heard It Through the Grapevine was uncomfortably reminiscent of Suzie Q from three years earlier, and the loop begins to close up. Relationships were complicated between John Fogerty and the other members of the band, who reproached the overbearing atmosphere he emanated, engendered by an steadily growing sense of self-importance. He wrote nearly all the songs, sang on them all, decided the arrangements and produced the albums. Even if Doug Clifford, Stu Cook and Tom Fogerty shaped an exceptional rhythm, it was John Fogerty that made it Creedence.

The second album from 1970, Pendulum, broadened the band’s musical palette a little, featuring keyboards, brass instruments, choirs and percussion. Put on the scale of rock music in general, this soul-oriented album is very good. Relative to Creedence’s success hitherto, a little less so. Apart from “Have You Ever Seen the Rain?”, a miracle melody, no song on Pendulum made it into the best of the band’s repertoire. Shortly after Pendulum’s release Tom Fogerty left the band, leaving the trio to devote themselves to the stage. The last album, Mardi Gras, came out in 1972 and tried to revive Creedence’s original scenery with a throwback cover, but the magic was no longer there. The three musicians finally had room for their democratic aspirations, taking turns writing and singing, but the band’s creative direction was lost along with Fogarty.

In terms of facts and wrongdoings, it’s impossible to ignore the terrible conflict that pitted John Fogerty against producer Saul Zaentz of the Fantasy label, which blighted John’s life. For twenty-five years after the separation, John Fogerty didn’t play any of Creedence’s songs. In the 80′s, he would switch the radio station whenever he heard a Creedence song – which was not an uncommon occurrence. To add insult to injury, he was sued for plagiarism by even his former record company, which accused one of his new songs of sounding too much like Creedence.

Others haven’t shied away from dipping into Creedence’s deep well of aesthetic inspiration. John Fogerty’s songs have been covered by Elvis, Tina Turner, Solomon Burke, Little Richard and hundreds of others. The first line-up of the yet-to-be Nirvana was a band focusing on Creedence covers. With its unpretentiousness, rejection of trends and rock’n roll circus, Creedence inspired the indie, punk and grunge rock of the decades that followed it. The band has become a model for root rockers of all generations, from Gun Club to Alabama Shakes including Ramsay Midwood, Marcus King, or simply Bruce Springsteen, an outspoken fan of Creedence covers. At the group’s induction into the Rock’n’roll Hall of Fame in 1993, he declared: “In the late ‘60s and early ‘70s, they weren’t the hippest band in the world. Just the best.”