Fidelio was Beethoven’s only opera. Or, more accurately, it is a Singspiel, like The Magic Flute, a generally fairly lighthearted opera interspersed with spoken passages. The libretto is a German adaptation of a drama by Jean-Nicolas Bouilly, Léonore ou l’amour conjugal, which Pierre Gaveaux had already set to music in 1798. Eerie similarities between Gaveaux’s and Beethoven’s scores suggest that the German may have heard the Frenchman’s work. But Leonore is a comic opera of the Ancien Régime whereas Fidelio looks forward, to pre-Romanticism.

Almost a decade would go by between the début of Beethoven's lyrical work in November 1805 – in its first draft and under the title Leonore – and the success of its reprise in May 1814. In the intervening years, the three-act libretto was boiled down to two more-dramatic acts, and no fewer than four overtures were written. The libretto developed a plot that would allow a discussion of the ideas of liberty and fraternity which the composer took from the Enlightenment, and which he transposed into love and marital fidelity, united in the face of arbitrary power’s yoke.

Fidelio on disc

Always contested, often little-loved by opera fans, Fidelio reaches beyond the stage to touch the universal, like Shakespeare's great works. Complaints commonly levelled against it often mention the absence of virtuosity or even awkwardness in the vocal writing; or a lack of theatricality. But a cursory glance at the score should be enough to dispel these arguments. Beethoven's construction is magisterial. Starting out like a lighthearted Singspiel, bit by bit the work takes on depth, arriving at a tragic dimension, which ends in general jubilation at the opening up of the prison, symbolising the end of obscurantism. It's rare for a work to have such a political conscience, or such noble aspirations.

Difficult to sing, Fidelio boasts some staggering roles, like Leonore-Fidelio, who moves from laughter to tears in an often-tense tessitura; and Florestan, non-existent throughout the first act, and who must suddenly wail his despair at the start of the following act, during the consuming night of his imprisonment. Some singers have shone in this opera; while others have cut their teeth on it... or their voices. Fidelio was committed to record rather late on: we find absolutely no trace of it before 1938 and the famous live recording made at the New York Metropolitan Opera, with the unforgettable Kirsten Flagstad, conducted by Artur Bodanzky (1938) and Bruno Walter (1941). Later on, there is Karl Böhm under the shadow of bombing at the Vienna Opera in 1944. There followed Toscanini, Klemperer and Furtwängler (of whom there exist numerous recordings) before the first studio versions in the early 1950s.

Mir ist so wunderbar

Gavin HardyGlorious Ancestors

Wilhelm Furtwängler (1950, 1953 live and studio)

For Wilhelm Furtwängler, Fidelio was a kind of grand humanist oratorio, close to the Ninth Symphony and the Missa Solemnis, which is obviously debatable from the point of view of style and chronology, but it's an interpretation which has brought forth some austere and profoundly human performances. Of all his versions, the best-remembered is surely the 1950 recording at Salzburg with Kirsten Flagstad, transformed twelve years after the Met, but with a voice that blends harmoniously with that of Elisabeth Schwarzkopf, who forms a young power couple with Anton Dermota.

On 12 October 1953, the same Furtwängler would conduct a memorable performance at the same Theater an der Wien where the work was first put on. Walter Legge, famous boss of EMI London, decided to record a studio version the day after that performance, with the same singers. This version remains legendary to the present day, because the artists all sang for the microphone with the same passion that they had brought to the stage the day before. We can, however, still regret the total absence of dialogues in this historic version.

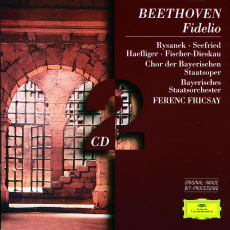

Ferenc Frisay (1957)

If we were only permitted to keep one of the older versions, even today, many people would still say that we should choose Ferenc Fricsay, first and foremost because the great Hungarian conductor (like Abbado after him) remembered that Fidelio has more in common with The Magic Flute than with Wagner. His conducting is alert, theatrical, fluid, and full of ardour. The voices here haven't been chosen out of deference to stardom, but on the basis of building a coherent artistic project. Ernst Haefliger is a moving Florestan and the young Leonie Rysanek is luminescent and sensual. Fischer-Dieskau, Irmgard Seefried and Gottlob Frick finish off a flawless distribution. And technical satisfaction is finally achieved thanks to DG, three years after the first efforts by Decca with Ernest Ansermet.

Otto Klemperer (1962)

With Klemperer, as with Furtwängler, it would be pointless to look for dramatic tension, as the two leaders share similar visions of the concert, or rather the oratorio, that is Beethoven's opera. EMI did everything that was possible at the time to make this the reference edition, with the best singers of the day: and in that they succeeded admirably. So no theatre in this version, but ideal incarnations by Jon Vickers, still one of history's greatest Florestans; Christa Ludwig, a mezzo Leonore-Fidelio with a warm timbre; Gottlob Frick, Franz Crass and Walter Berry rounding out this high-class distribution. However, Klemperer's imperturbable and slow conducting style weighs rather heavily on the whole.

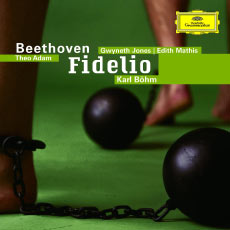

Karl Böhm (1969)

This writer admits a certain weakness for this version recorded to mark the bicentenary of Beethoven's birth, offered by DG as part of its end-of-year subscription as part of its monumental complete works of Beethoven in 1970. It's the fourth and final record by this great conductor of this opera, with which he re-opened the Vienna Opera after the war. Böhm has a tiger in his tank as he leads the imposing Dresden Staatskapelle flawlessly through this splendid studio version. Everything here is theatrical, ardent, urgent. Gwyneth Jones is an utterly heroic Leonore; James King a radiant Florestan; Theo Adam a cruel Pizarro; Franz Crass a weak and human Rocco; Martti Talvela (no less!), a dazzling minister; and Peter Shreier and Edith Mathis make a touching young couple. The choir of the Leipzig Radio and of the Dresden Opera are spellbinding. And on top of all that, we get an extroverted, high-voltage rendition of the overture Leonore III.

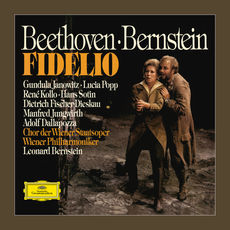

Leonard Bernstein (1978)

As he was wonted to do, Bernstein offers here his own particular vision of Beethoven's masterpiece, in a style that few would have expected from him: lightened and moving the work towards its Mozartian origins. The ebullient American sometimes showcases contrasts, but they always tend in the direction of the theatrical, with excellent singers and remarkably well-staged dialogues. Recorded in Vienna with the shimmering colours of the Philharmoniker, the distribution includes a Gundula Janowitz who is far from the placidity for which she has sometimes drawn criticism; René Kollo (a great Wagnerian voice) as a noble Florestan and Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau's minister is... imperious.

Our Contemporaries

Bernard Haitink (1990)

No-one would have pictured Jessye Norman as Leonore-Fidelio on stage, but this record contains a magisterial performance by her as Beethoven's heroine, with one of the century's greatest conductors. The beauty and power of her timbre, mixed with an incredible vocal facility, create a spellbinding dramatic character. It is a joy to hear her great aria (Abscheulicher) sung with such utter perfection and accompanied by a velvety orchestra (the Dresden Staatskapelle, who had already made a magnificent recording of this work with Böhm in 1969) under the attentive and subtle leadership of Bernard Haitink. Tenor Reiner Goldberg is a spirited Florestan, although he lacks the youthful sheen and golden voice of Jonas Kaufman, whose career had not yet begun by this point. This was assuredly one of the great recordings of the early 1990s.

Nikolaus Harnoncourt (1994)

The version from the "pope" of historically-accurate performances had naturally been long-anticipated. The moment came with this recording made in 1994, which was quickly hailed by critics for the clarity of its textures, for its theatrical efficiency and for the clear and dynamic woodwind sound from the Chamber Orchestra of Europe. However, some of these tempos are either too quick or too slow, judging by the numbers on the score and by conventional standards. This is the eternal dilemma of "authenticity", which doesn't exist in musical interpretation, and which is generally a projection made by contemporaries. As for the singers, this version doesn't disappoint: even while the era doesn't boast the stars of other times, the distribution is even and matches the intentions of the conductor, who reigns supreme on this recording.

Daniel Barenboim (1999)

It shouldn't come as a surprise that this opera is such a good fit for the great humanist Daniel Barenboim. He is very familiar with Beethoven's only opera. He has conducted it many times, most notably in Berlin and Paris, with Stéphane Braunschweig producing, in 1995. His 1999 performance was recorded over the course of several nights, the pleasant sound engineering values express the pure and expressive direction of the piece. It is regrettable, however, that much dialogue is missing from the record. Placido Domingo's radiant timbre gives his Florestan a realistic quality, as the story is said to be taking place around Seville. For Barenboim, Fidelio is above all a story of love and courage with politics as the backdrop, and not the other way around. He still uses the Leonore II overture to open the opera, to underline Beethoven's modernity: this overture sets out themes that we'll only hear later on in the score, in an anticipation of Wagner's work.

Sir Simon Rattle (2003) and Claudio Abbado (2010)

Among the recordings from the early 21st Century, we will name in particular those by Sir Simon Rattle and Claudio Abbado. While very different, each has its own opposing attractions. Sir Simon seems to hear the fabulous qualities of "his" Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra, which was once directed by... Claudio Abbado, to the detriment of a distribution which is in fact not very exceptional. So what we are offered by the English conductor is a stunning demonstration of orchestral skill.

Claudio Abbado's version offers, first and foremost, a vision: it sets Fidelio in the brilliant furrow ploughed by The Magic Flute, as Ferenc Fricsay once did – and indeed, in a sense – Daniel Barenboim. Recorded in a semi-staged concert during the 2010 Festival of Lucerne, this Fidelio enjoys a radiant, warm humanity. The ephemeral, diaphanous orchestra is made up, as ever, from the finest musicians of several European orchestras, joined by the musicians of the Mahler Chamber Orchestra.

A superb distribution with the warm, easy timbre of the Swedish soprano Nina Stemme alongside Jonas Kaufmann's Florestan, who begins his aria in a spectacular style, with a crescendo as spellbinding as it is daring. He underlines the despondency and fragility of his character, who is already feeling the menacing breath of a violent and unjust death. The rest of the distribution is very much in keeping with this clear, simple, refined recording from a conductor who has nothing left to prove. One of the very great modern versions of this difficult opera, but not as much of a hybrid as some describe it even today.

To finish, here are a few curiosities which may be to your taste. We recall the precious recording of Léonore ou l’amour conjugal, written in 1798 by Pierre Gaveaux, now available exclusively as a DVD recording of its stage performance. Its musical interest outstrips its value as a historical curiosity.

Leonora, the ill-fated opera by Ferdinando Paër (which Beethoven wanted to set to music), was recorded in 1978 by the great Mozartian Peter Maag: a world first. It was he who found the score in a library in the composer's home-town of Parma.

Pierre Gaveaux: Léonore, ou L’amour conjugal (excerpts)

Cultural MediaA brilliant distribution brings together Edita Gruberova, Giorgio Taddeo, Siegfried Jerusalem and the Bavaria Symphony Orchestra. The first draft of Beethoven's work, Leonore was met with lively interest when it was released in two complementary versions. The first, an indefatigable timeless classic conducted by Herbert Blomstedt with the Dresden Staatskapelle, the second on period instruments under the incisive and educated hand of John Eliot Gardiner.

This is a document of a bygone time, when operas were sung in the language of the players. This recording of Fidelio, in French, was conducted by Désiré Emile Inghelbrecht in 1953. It holds plenty of musical interest too, as a record of a certain kind of French singing and a conception of the art which has now disappeared. Let’s finish our panorama with a version of wordless extracts in an arrangement for wind instruments, something very popular in the early 19th Century and called Nachtmusik.