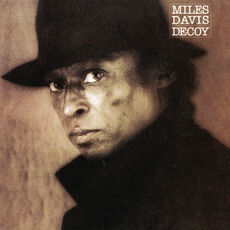

Driven by a lifeblood of constant change, jazz depends on ever-evolving combinations of voices and visions to spark its creative verve. Miles Davis, to name the most obvious example, was a master at making and remaking ensembles. Over the years many talented players passed through his ever-changing circle of players including guitarist John Scofield in the 1980s, who stuck around long enough to be part of three Davis records from the decade: Star People, Decoy and You’re Under Arrest.

Before and after his time with Davis, Scofield (better known as "Sco" to friends and fans) went on to form and reform his own small groups. Over the years, two veteran instrumentalists have been a constant presence in those evolving crews: bassist Steve Swallow and drummer Bill Stewart. Swallow (life partner of pianist/composer Carla Bley), first came into Scofield's orbit when both were at the Berklee College of Music in Boston in the early' 70s—Scofield as a student and Swallow as a teacher. Fast friends as well as musical collaborators, this talented trio and in particular its masterful bassist, are now being celebrated in a new Scofield ECM recording, Swallow Tales.

"With other people you think well, I can't do that with them because they hate that kind of music and they'll think I'm a jerk for even suggesting it," said Scofield recently to Qobuz. "But as a player and also as a person, Steve is very giving and open and always up for whatever you want to try." Swallow started his playing career in Dixieland jazz bands at Yale University, rubbing elbows with great swing players like Buck Clayton and Rex Stewart, who'd been forced by changing tastes to play a style of music that was the party music before rock and roll appeared. It was also at Yale that his friend woodwind/keyboard player Ian Underwood (who would later join Frank Zappa in The Mothers of Invention) first introduced Swallow to the music of Ornette Coleman. Using that knowledge, Swallow moved from reading music on the bandstand to playing in improvisational jazz groups led by Jimmy Giuffre, Art Farmer, Gary Burton, Zoot Sims, Jim Hall and Stan Getz. In the early '70s he became one of the first big name jazz bass players to make the switch from acoustic standup bass to the electric instrument.

"He just said it's the instrument of the future and I'm gonna play it," recalls Scofield of the then mildly controversial move. "He plays it with a pick which is totally weird, all the other great electric bass players use their fingers. And he's a super melodic soloist almost like a horn player, like Lester Young or Stan Getz and the guys he really likes who are real melody players."

As one of today's three dominant jazz guitarists along with Pat Metheny and Bill Frisell, John Scofield chose Swallow Tales' set list mostly by selecting familiar tunes from the Swallow songbook that he and their composer know by heart. The result is nothing fancy - just loose, conversational, easy-to-appreciate post-bop.

"A lot of these tunes I learned back in the '70s when I was really trying to learn how to play jazz… actually I'm still trying to learn how to play jazz!" Scofield says, timing his moment of self-deprecation for maximum comedic effect. "Because I've known them for so long, it was almost like we were doing a record of standards. While the bad part of that is that everyone has done them eight zillion times, it can also mean that everybody can subconsciously get into all kinds of cool stuff that they wouldn't get into when playing new original music. Here because of our gut reactions to what's going on, you can hear us bringing out new stuff, pulling new things out of ourselves. It's a spur of the moment thing."

To amplify this sense of discovery, the recordings heard on Swallow Tales are all whole takes, recorded in four hours with minimal rehearsal time. In most cases a head arrangement was run through before each tune was recorded twice by engineer Tyler McDiarmid at NYU's Steinhardt School of Music. Drummer Stewart, a quick study, learned the tunes he didn't know on the fly before the album was recorded.

"When he plays, you can tell he really knows the changes, he understands modern jazz harmony," Scofield says of the drummer. "It comes through in his playing, how he can shade things and have a dialogue with you. Bill can somehow push the music in great ways and make the band come alive. So many nights when somebody takes a solo, his will be the most musical and it's on the drums, an instrument without exact pitches!"

Stewart has also been a key part of the funky side of Scofield's career which the guitarist agrees may well be the most influential part of his legacy. While Metheny has dabbled in New Age music, and worked with talents as diverse as David Bowie and Joni Mitchell, and Frisell's endlessly eclectic gifts have proven adept at literally everything he tries from surf guitar to Charles Ives and experimental Nashville, Scofield has shown a sustained interest and genuine flair for soul jazz.

Rooted in blues, gospel and R&B and fortified by the Hammond B-3 organ, soul jazz blended jazz improvisation with accessible rhythms. As soul music from labels like Stax, Atlantic and Motown crossed over to larger and larger audiences, performers like trumpeter Donald Byrd, tenor saxophonist Joe Henderson and alto saxophone player Julius "Cannonball" Adderley took notice and began incorporating it in their recordings, which were tastefully funky and transformed jazz into dance music for the first time since the big bands. Criticized by the same predictable jazz snobs who consider jazz-rock fusion to be heresy, soul jazz was slagged for being too pop, too easy to relate to—damning evidence of a sell out. However, when you listen to the tasty fills and the way Scofield's grooves drive the proceedings on solo albums like 1993's Hand Jive, 1995's Groove Elation, 1998's A Go Go (with Medeski, Martin & Wood) and 2003's Up All Night, it's clear that soul music speaks to Scofield and what he wants to say as an artist. Not surprisingly, the guitarist disputes the contention that soul jazz is overly simple, and so somehow less important than bebop or more complex jazz.

“I’m very proud of that work. I used to go hear those guys play live and I loved [organist] Jimmy Smith. And [tenor saxophone player] Stanley Turrentine—it seemed like it just couldn’t get better than that!” says Scofield. “When you hear Les McCann and Eddie Harris on Swiss Movement; When you hear the best Weather Report shit; When you hear Miles play over a groove like that. And Herbie’s Headhunters! Without using the ‘J’ word, there is some very deep stuff there that you can’t categorize as anything other than great, improvised groove music. If you’re not going to call it jazz, what the fuck are you going to call it? Because if it wasn’t for jazz, that music wouldn’t exist.”