Mozart’s rise to popularity is often dated from the sesquicentenary of his death, in 1941. But even before that watershed, a few noble souls took him seriously, and not least among them were two remarkable German brothers, the conductor Fritz Busch and the violinist and composer Adolf Busch.

They were born in Siegen, Westphalia, Fritz on 13 March 1890 and Adolf a year later. Their father Wilhelm made and repaired stringed instruments: the boys had the run of his shop and learnt to play tiny fiddles he had made. Even as a toddler, Fritz would set up several chairs in a row and stand before them on a footstool to conduct an imaginary orchestra. Soon he gravitated to the piano while Adolf kept to the violin. At weekends they would accompany Wilhelm on treks round the Rhineland pubs and clubs, playing for dancing. Far from putting them off, this rough and ready training gave them a fierce love for music. In 1902 Adolf, who had found a patron, entered the Cologne Conservatory; and Fritz followed in 1906, studying harmony and counterpoint with Otto Klauwell, piano with Karl Boettcher and Lazzaro Uzielli – a pupil of Clara Schumann – and conducting with Brahms’s favourite interpreter Fritz Steinbach. He became a good enough pianist to be Adolf’s regular sonata partner until the early 1920s, and he played the instrument to the end of his life; but conducting was his goal. He learnt much from observing Steinbach, Arthur Nikisch and Felix Weingartner.

On 28 December 1908 Busch made his public conducting debut at Trier. His rise was rapid: Riga (1909); summers at Bad Pyrmont (1909-12); Gotha (1911-12); Aachen (1912-18, with a break for war service); Stuttgart (1918-22); and Dresden (1922-33). He was especially associated with Mozart and with the Verdi revival.

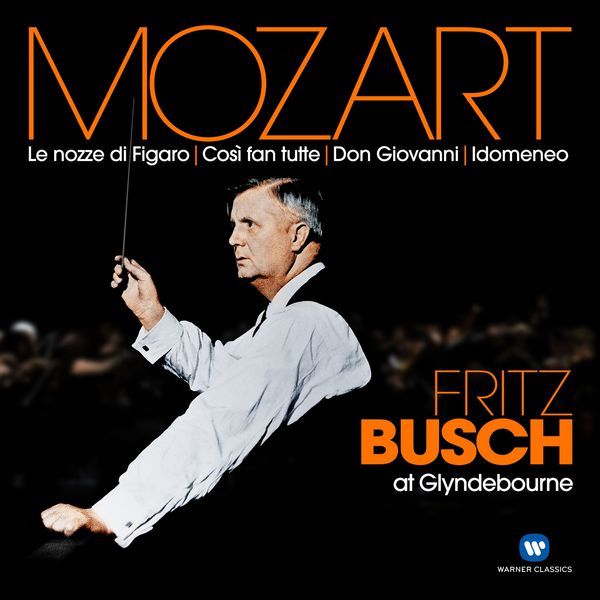

In 1932 he collaborated with Carl Ebert in Mozart’s Die Entführung at Salzburg, and later that year they presented Un ballo in maschera at the Berlin Städtische Oper with sets by Caspar Neher, to acclaim. On Hitler’s coming to power in 1933, Busch was ousted from Dresden and, like his brother Adolf, felt obliged to leave Germany. He went first to Buenos Aires, to conduct the German part of the opera season and a concert series at the Teatro Colón: he was a welcome visitor from then on and even took Argentine citizenship. Copenhagen, where he made his home, and Glyndebourne also predominated in Busch’s career: he helped to build up the Danish State Radio Symphony Orchestra; and with the Glyndebourne summer festivals, which he and Ebert directed from 1934, he changed the face of opera in Britain. From 1937 Busch was also chief conductor of the Konsertföreningen in Stockholm. In 1940, after a triumphant run of Così fan tutte at the Royal Opera there, he and his family travelled via Moscow, Vladivostok and Japan to Buenos Aires; and for the rest of the War he worked in South or North America. In 1941-42 he joined the New Opera Company in New York and gave concerts with the Philharmonic-Symphony. In 1945 he made the first of 69 Metropolitan Opera appearances.

At the War’s end, he went back to Stockholm for opera and Copenhagen for concerts. In 1950 he returned to Glyndebourne, scored a triumph at the Edinburgh Festival with his Danish orchestra and made his Vienna State Opera debut with Otello. In February 1951, on his first visit to Germany for almost 18 years, he conducted concerts in Hamburg and Cologne, as well as a recording of Un ballo in maschera for the Radio. That summer at Glyndebourne he presided over all three Mozart-Da Ponte operas and Idomeneo. His last appearances were made with the Glyndebourne company at the 1951 Edinburgh Festival: fittingly he conducted Verdi and Mozart and his final performance was of Don Giovanni. Six days later, on 14 September, he died suddenly in London.

Create a free account to keep reading